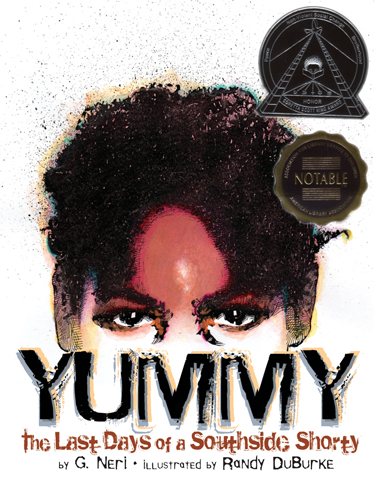

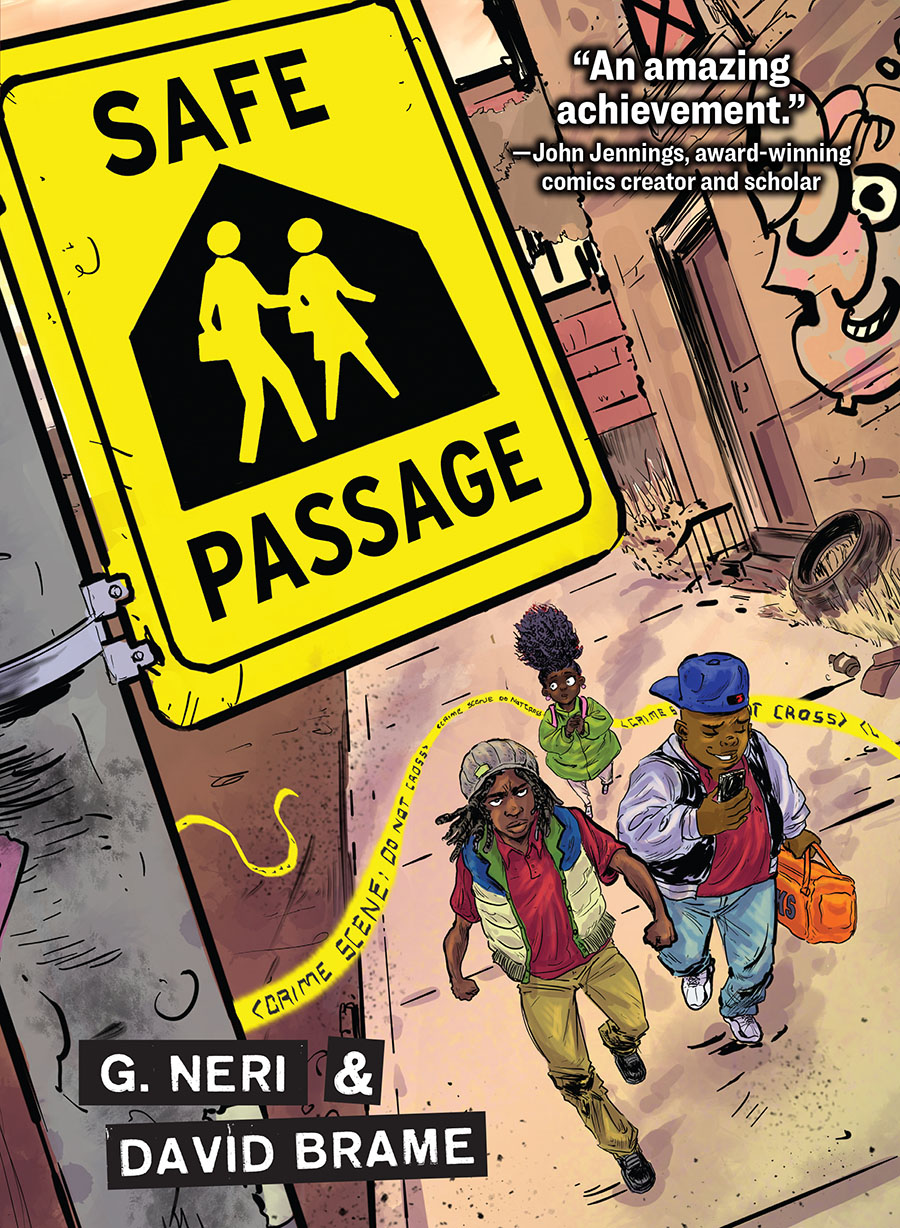

It’s been 15 years since the publication of Yummy: The Last Days of a Southside Shorty by G. Neri, illustrated Randy DuBurke. Thousands of readers — both young and old — have been touched by Yummy’s story since then. It’s even led to a cousin, born 14 years later: Safe Passage, also by G. Neri, illustrated by David Brame.

This award-winning graphic novel continues to find new readers, keeping the name and memory of Robert “Yummy” Sandifer alive. Lee & Low sat down with author G. Neri to talk about its impact, and how it has led to who he is as a writer today.

By G. Neri, illustrated by Randy DuBurke

CORETTA SCOTT KING AUTHOR AWARD HONOR

⭐4 STARRED REVIEWS⭐

⭐"Framing the story through the eyes and voice of a fictional character, 11-year-old Roger, offers a bittersweet sense of authenticity while upholding an objective point of view. . . the exploration of 'both sides of the story' is unflinchingly offered." —School Library Journal, starred review

By G. Neri, illustrated by David Brame

BLACK CAUCUS OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION (BCALA) CHILDREN & YOUTH LITERARY AWARDS WINNER

⭐"Somber with a sprinkling of optimism and a firm grounding in unconditional familial love." —Kirkus Reviews

Q&A With G. Neri

Congratulations on 15 years since the publication of Yummy. How have things changed for you as a writer since its release?

Well, Yummy was my first book. I am now working on my 20th. Yummy made me a writer in every sense. I didn’t know it would have the impact that it has and that it would still be selling and I would still be talking about it in schools 15 years later!

If you could go back to the time when you were writing Yummy, what piece of advice would you give yourself?

It started off as a film project since I was a filmmaker at the time the real story happened. I was doing storytelling workshops in inner city schools at the time and I could see the reaction the real story had on students I was talking to who were in the middle off their own gang war in South Central LA. I knew Yummy’s story had to be told, but every time I got close to turning it into a movie, something felt off—there was a better way to tell it. I didn’t know it’d become a graphic novel. It took me years to figure that out. I guess I’d tell myself to be patient—or just say: it’s a graphic novel, dummy! I might have saved myself some years.

Is there a favorite memory you have from Yummy‘s publication?

I have had so many extraordinary experiences with this book. Teachers always say that when their class reads it, its so quiet you can hear a pin drop. Librarians tell me its their most stolen book, that’s kids can’t give it up. I have seen students literally fighting over a copy that just came in since its always checked out. The book has changed lives in ways I didn’t think possible. I’ve had blind students read it with incredible insight. Whenever I talk about it in school the energy changes immediately—they become hyper focused and it brings out all kinds of deep emotions. I’ve seen it turned into plays and dance and art and fan fiction. It cuts through everything and gets to the heart of the matter.

It’s been 31 years since Yummy’s premature death. How, in your view, have things changed for Chicago youth since then?

What’s happened became the basis and the reason for a follow-up book, Safe Passage. The 3 big gangs that ran the city were broken up, projects torn down, inner city schools closed and consolidated. But instead of a central authority running the gangs, over 800 micro-gangs formed, making the problem much more complex and dangerous.

In 2024 you released Safe Passage, a graphic novel that also follows Southside Chicago youth. One could consider it a cousin to Yummy. What made you return to this location and subject? Did you approach this one differently than Yummy?

I saw a video about a father, a veteran of the Irag war, and how he dealt with his kids going to school everyday in the Southside. His kids, like so many, had to walk 15 minutes to school every day. But they had to cross 3 different gang territories to do so. Because they were living in a certain neighborhood, they were affiliated with the gang in that neighborhood, making them a target. The father saw their journey as dangerous as running the gauntlet in Fallujah during the war. He had to teach his kids the survival tactics he’d learned in the war. Out of that was born the Safe Passage program where ex-vet and concerned adults manned safe passages to school and back, just so students wouldn’t be killed in the line of fire. I wanted to tell a compressed story, one that takes place in a single day where we discover what happens when you stray from the safe passage. An epic journey of survival told from sunrise to sunset.

If Yummy were still alive today, where do you think he would be now? What’s one piece of advice you think he would give to today’s youth?

I couldn’t begin to imagine that. Students have tackled that question and written all kinds of scenarios. You can look to the two brothers who were imprisoned for his death. In many ways, they were victims of the gang life as well. Since their release they have spoken out against their actions. Many shorties at the time couldn’t imagine life after 19. I would hope he’d find a way out but it’d be naïve to think he could just change. Had he been jailed for Shavon’s death, maybe he’d have the same reaction as his killers and become a spokesperson against the gang life. In a way, that’s what this book has done—taken something tragic and turn it into something positive: a vehicle to witness and discuss what really happens out there on the streets.