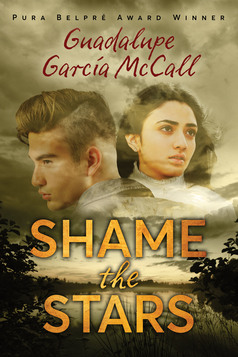

This week, in acknowledgement of Columbus Day/Indigenous ![]() Peoples’ Day, we are offering a series of blog posts that look at pieces of history that have been hidden, silenced, altered, or swept under the rug. Today we share author Guadalupe García McCall’s reflections on her discovery of a startling piece of Texas history. This piece was originally published as the Author’s Note in her new novel, Shame the Stars.

Peoples’ Day, we are offering a series of blog posts that look at pieces of history that have been hidden, silenced, altered, or swept under the rug. Today we share author Guadalupe García McCall’s reflections on her discovery of a startling piece of Texas history. This piece was originally published as the Author’s Note in her new novel, Shame the Stars.

A few years ago, my eldest son, James, was taking a college history course. He was in his room one night, studying, when he suddenly burst into our living room holding a book and asking, “Mom! Do you know what happened to our people?”

I was sitting on the couch with my husband at the time. His family is Scotch-Irish American, so I looked at my husband then back at my son and asked, “Which people?” Well, he was talking about us, me and him and our side of the family. He held in his hands a copy of Benjamin Heber Johnson’s book, Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and Its Bloody Suppression Turned Mexicans Into Americans. He sat on the couch that evening and showed me horrible pictures and shared terrible details while I flipped through the pages appalled by what happened to Tejanos (Mexican Americans) and Mexicans in Southern Texas in 1915, at the time of the Mexican Revolution. These were things my father had talked about, but which had meant very little to me as a child as I had never heard of them anywhere else other than at home, when my father was storytelling.

That day on the couch, I became the student as my son explained the discovery of the Plan de San Diego, a manifesto written in 1915 by Mexican radicals calling for the up rise of a “Liberating Army of Races and Peoples.” The manifesto was brought into the Unites States through South Texas territory in January by Basilio Ramos and urged US-born Mexicans, immigrants, Indigenous people, and Blacks to join the Mexican Revolution and help reclaim Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, California, and Colorado. The plan outlined a process in which Texas would become its own republic and later would seek annexation from Mexico. In February, less than a month later, a second copy of the manifesto would be discovered and the lives of Tejanos and Mexicans in South Texas would change forever.

The discovery of the Plan de San Diego came with many conflicts, most of which were fueled by political agendas. However, the human factor had much to do with the horrific crimes that were committed against Tejanos and Mexicans in South Texas at that time. The racial tensions that had long existed in the region were heightened by local politics, misappropriated lands, and acts of rebellion as more and more Tejanos became disenfranchised. Losing their properties, farmlands, and ranches to the increasing number of Anglo immigrants, Tejanos became field hands and peons in the very land their parents and grandparents had owned and cultivated for generations in the United States.

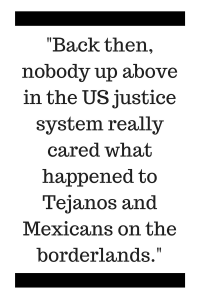

As tensions rose between Tejanos and Anglos, more political and social issues came into play, and soon shoot-outs, explosions, and other, more violent, acts of insurgence from Tejanos and Mexicans became the norm. The Texas Rangers, along with local authorities, tore through the territory enforcing vigilantism, their own brand of swift and lethal justice, in an attempt to enforce the law in South Texas. The lynchings, executions, fusillades, round-ups, and draggings of Tejanos and Mexicans in South Texas only served to fuel the rebellion. The insurgence and its punishment became a vicious cycle that was too horrific to be spoken of, much less documented. Many of the crimes committed against Tejanos and Mexicans in South Texas went unreported. Most have been forgotten.

No one can ever do justice to the retelling of the extent of the horrific atrocities committed during that time with complete accuracy and authenticity because so much of it was concealed, poorly recorded, or swept under the proverbial rug. Back then, nobody up above in the US justice system really cared what happened to Tejanos and Mexicans on the borderlands. Nobody in Washington worried about us or our plight at the hands of the Texas Rangers. There were those of us who would speak for our people, tell of our woes. Reporters like Jovita Ituarte, aka A. V. Negra, who wrote for her father’s paper, La Cronica, tried to  illuminate the plight of Tejanos and Mexicans in those times. However, her father’s small paper, written in Spanish, at a time when only Tejanos and Mexicans read Spanish text circulars, went unread by those who might have made a difference, those whose jobs it was to protect us, those who chose to turn a blind eye to us in our ever-darkening, small corner of the world.

illuminate the plight of Tejanos and Mexicans in those times. However, her father’s small paper, written in Spanish, at a time when only Tejanos and Mexicans read Spanish text circulars, went unread by those who might have made a difference, those whose jobs it was to protect us, those who chose to turn a blind eye to us in our ever-darkening, small corner of the world.

Suffice it to say, I went to my room that night, after listening to my son go on and on about the Plan de San Diego and what it means in the scope of American history, unable to get those pictures out of my mind. I wanted to inform myself, so I took Johnson’s book with me to read in bed, but time and time again I kept turning back to the picture of Rangers dragging the bodies of alleged Mexican bandits through the brush. That such a picture would become a postcard that people bought and mailed to their loved ones is incomprehensible to me. All I can think when I see that picture is that those men and boys had mothers, and as a mother of three boys, my heart aches for the loss of them. I thought about the Texas Rangers’ motto to shoot first and ask questions later if the person of interest was a Mexican, and I wept for all the mothers whose innocent sons were killed in the name of justice. I wept for all the brothers and sisters, all the tios and tias, the padrinos, the primos, the novias, the amigos, the vecinos . . . all the gente, the people, who suffered because of the discrimination and abuse of Tejanos and Mexicans at the hands of the Texas Rangers and the lawmen who joined them and formed possés killing indiscriminately, summarily, because the color of our skin dictated they could.

So why didn’t I know this part of my culture’s history? Well, a long,  long time ago I was a small child, and like many a small child in America I read textbooks that did not include these horrific events in American history. Why don’t I know much more now after doing all this research? History books being published and printed for American schools today still make no mention of this part of our history. Perhaps textbook publishers find this topic too controversial. Or maybe they are just worried about what might happen if we educate ourselves with truthfulness. I can’t begin to answer that question.

long time ago I was a small child, and like many a small child in America I read textbooks that did not include these horrific events in American history. Why don’t I know much more now after doing all this research? History books being published and printed for American schools today still make no mention of this part of our history. Perhaps textbook publishers find this topic too controversial. Or maybe they are just worried about what might happen if we educate ourselves with truthfulness. I can’t begin to answer that question.

What I can do I have done. I’ve included in this book a small ofrenda, a different point of view—a rebellious, contentious voice—along with a small sampling of source materials, both fiction and nonfiction, so that American students might be able to cull through them and better educate themselves. My hope is that students of any and all ethnicities and cultures begin to understand the difference between primary and secondary sources, valid and unreliable sources, all of whose distinction they must learn to assess and categorize as they venture to study, appraise, and discover their ancestral identity and presence in historical documents in the minefield that is the Internet. May my book, Shame the Stars, open up important and truthful conversations with teachers, family, and friends. May this book give them something to consider, something to research, something to push against when they encounter injustice. May this book help them pave the way to a better tomorrow.

Some book recommendations for teachers and mentors:

Anglos & Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1987 by David Montejano, University of Texas Press, 1987

From Out of the Shadows, Mexican Women in Twentieth-Century America by Vicki L. Ruiz, Oxford University Press, 2008

Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion and Its Bloody Suppression Turned Mexicans Into Americans by Benjamin Heber Johnson, Yale University Press, 2005

River of Hope: Forging Identity and Nation in the Rio Grande Borderlands by Omar S. Valerio-Jimenez, Duke University Press Books, 2013

Guadalupe Garcia McCall was born in Mexico and moved to Texas as a young girl, keeping close ties with family on both sides of the border. Trained in Theater Arts and English, she now teaches English/Language Arts at a junior high school. Her poems for adults have appeared in more than twenty literary journals. McCall is an up-and-coming talent whose debut YA novel, Under the Mesquite, won the Pura Belpré Award and was named a Morris Award finalist. McCall lives with her husband and their three sons in the San Antonio, Texas, area. Her newest novel is Shame the Stars. You can find her on the Web at guadalupegarciamccall.com.

Guadalupe Garcia McCall was born in Mexico and moved to Texas as a young girl, keeping close ties with family on both sides of the border. Trained in Theater Arts and English, she now teaches English/Language Arts at a junior high school. Her poems for adults have appeared in more than twenty literary journals. McCall is an up-and-coming talent whose debut YA novel, Under the Mesquite, won the Pura Belpré Award and was named a Morris Award finalist. McCall lives with her husband and their three sons in the San Antonio, Texas, area. Her newest novel is Shame the Stars. You can find her on the Web at guadalupegarciamccall.com.