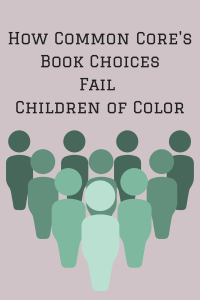

The Common Core has become a hot-button political issue, but one aspect that’s gone lar![]() gely under the radar is the impact the curriculum will have on students of color, who now make up close to 50% of the student population in the U.S. In this essay, Jane M. Gangi, an associate professor in the Division of Education at Mount Saint Mary College and Nancy Benfer, who teaches literacy and literature at Mount Saint Mary College and is also a fourth-grade teacher, discuss the Common Core’s book choices, why they fall short when it comes to children of color, and how to do better. Originally posted at The Washington Post, this article was reposted with the permission of Jane M. Gangi.

gely under the radar is the impact the curriculum will have on students of color, who now make up close to 50% of the student population in the U.S. In this essay, Jane M. Gangi, an associate professor in the Division of Education at Mount Saint Mary College and Nancy Benfer, who teaches literacy and literature at Mount Saint Mary College and is also a fourth-grade teacher, discuss the Common Core’s book choices, why they fall short when it comes to children of color, and how to do better. Originally posted at The Washington Post, this article was reposted with the permission of Jane M. Gangi.

Children of color and the poor make up more than half the children in the United States. According to the latest census, 16.4 million children (22 percent) live in poverty, and close to 50 percent of country’s children combined are of African American, Hispanic, American Indian, Asian American heritage. When the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) were introduced in 2009—2010 , the literacy needs of half the children in the United States were neglected. Of 171 texts recommended for elementary children in Appendix B of the CCSS, there are only 18 by authors of color, and few books reflect the lives of children of color and the poor.

When the CCSS were open for public comment in 2010, I (Gangi) made that criticism on the CCSS website. My concerns went unacknowledged. In 2012, I presented at a summit on the literacy needs of African American males, Building a Bridge to Literacy for African American Male Youth, held at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. Emily Chiarello from Teaching Tolerance acknowledged the problem and connected me with Student Achievement Partnership, an organization founded by David Coleman and Sue Pimental, “architects” of the English Language Arts standards.

In the fall of 2012, representatives from Student Achievement Partnership came to Mount Saint Mary College in Newburgh, New York, to ask our Collaborative for Equity Literacy Learning (CELL) to help right the wrong. SAP wanted us to provide an amended Appendix B. In July 2013, CELL presented SAP with a list of 150 multicultural titles, which were recommended by educators from across the country and by more than thirty award committees. All the books were annotated and excerpts were provided. The 700+ PowerPoint slides of the project can be found here. SAP then sent the project to Stanford University’s Understanding Language Program for validation of text complexity. The Council of Chief State School Officers has yet to make the addition to the CCSS website.

Why does seeing themselves in books matter to children? Rudine Sims Bishop, professor emerita of The Ohio State University, frames the problem with the metaphor of “mirror” and “window” books. All children need both. Too often children of color and the poor have window books into a mostly white and middle- and-upper-class world.

This is an injustice for two reasons.

One is rooted in the proficient reading research. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, researchers asked, “What do good readers do?” They found that good readers make connections to themselves and their communities. When classroom collections are largely by and about white people, white children have many more opportunities to make connections and become proficient readers. Appendix B of the CCSS as presented added to the aggregate that consistently marginalizes multicultural children’s literature: book lists, school book fairs and book order forms, literacy textbooks (books that teach teachers), and transitional books (books that help children segue from picture books to lengthier texts). If we want all  children to become proficient readers, we must stock classrooms with mirror books for all children. This change in our classroom libraries will also allow children of the dominant culture to see literature about others who look different and live differently.

children to become proficient readers, we must stock classrooms with mirror books for all children. This change in our classroom libraries will also allow children of the dominant culture to see literature about others who look different and live differently.

A second reason we must ensure that all children have mirror books is identity development. For African American children, Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. are not enough. They must also see African-American artists, writers, political leaders, judges, mathematicians, astronauts, and scientists. The same is true for children of other ethnicities. They must see authors and illustrators who look like them on book jackets. Children must be able to envision possibilities for their futures. And they must fall in love with books. Culturally relevant books help children discover a passion for reading.

I (Benfer) was one of the annotators for the project. Each year I tell my incoming fourth-grade students, “None who enter here remain unchanged” (from Brandon Mull’s Fablehaven). Participating in this project made this statement come true for my students and me. Before working to amend Appendix B, I had been teaching for 16 years, and had always been serious about my classroom library.

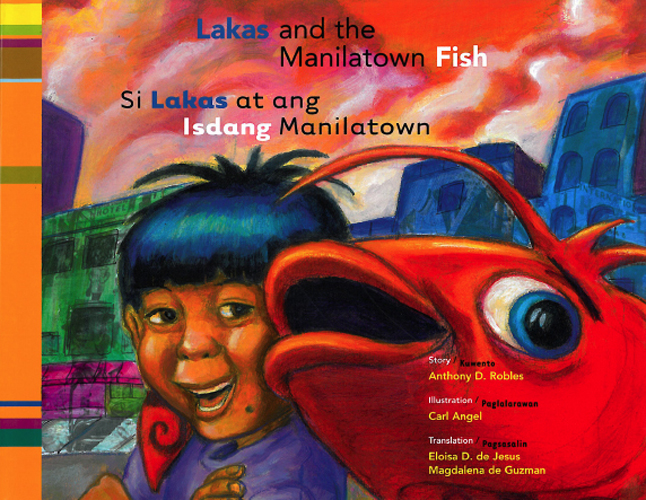

Reading a great book changes us. I had not yet encountered the metaphor of mirrors/windows until hearing Gangi’s talk in our children’s literature course, based on her article “The Unbearable Whiteness of Literacy Instruction.” After the talk I  found myself reflecting on the books to which I was exposing my students. I expanded my library to include many texts reviewed in the project, which allowed my students to see the wonderful diversity in the world. As my classroom library grew, my students began to read and discuss these diverse texts I began to hear students say things like, “I like books which have a black main character,” and parents emailed me to say, “I just wanted to say thank you for acknowledging Black History Month and having such a wonderfully diverse reading library for fourth grade.” Filipino students gave me a standing ovation when I purchased Anthony D. Robles and Carl Angel’s Lakas and the Manilatown Fish/Si Lakas at ang Isdang Manilatow (see Lee & Low Books for this and other multicultural books.)

found myself reflecting on the books to which I was exposing my students. I expanded my library to include many texts reviewed in the project, which allowed my students to see the wonderful diversity in the world. As my classroom library grew, my students began to read and discuss these diverse texts I began to hear students say things like, “I like books which have a black main character,” and parents emailed me to say, “I just wanted to say thank you for acknowledging Black History Month and having such a wonderfully diverse reading library for fourth grade.” Filipino students gave me a standing ovation when I purchased Anthony D. Robles and Carl Angel’s Lakas and the Manilatown Fish/Si Lakas at ang Isdang Manilatow (see Lee & Low Books for this and other multicultural books.)

I recommended Rukhsana Khan’s Wanting Mor, the story of a young girl in Afghanistan to one of my students (see Groundwood Books for this and other multicultural books). This student’s parents were astounded by the change in their daughter. She had been an uninterested reader and was transformed into an enthusiastic one. She began to request copies of books featuring girls in Afghanistan. The students and I spent countless hours creating lists of recommended texts.

What do we do with this issue now, educators? The CCSS have yet to adopt the expanded and enhanced Appendix B, but the message is too important to be filed away. This work must be must shared with educators. The expanded Appendix B contains recommended texts that are mirrors and windows for our students’ worlds.

“None who enter here remain unchanged.” Teaching Tolerance will be publishing the list in the near future. In the meantime, children of the United States are waiting for us to make this change for the better.

Jane M. Gangi is an associate professor in the Division of Education at Mount Saint Mary College in Newburgh, New York. Nancy Benfer teaches literacy and literature at Mount Saint Mary College and is a fourth-grade teacher at Bishop Dunn Memorial School. Gangi is the author of three books: “Encountering Children’s Literature: An Arts Approach,” “Deepening Literacy Learning: Art and Literature Engagements in K-8 Classrooms (with Mary Ann Reilly and Rob Cohen),” and “Genocide in Contemporary Children’s and Young Adult Literature: Cambodia to Darfur.” Both are members of the Collaborative for Equity in Literacy Learning at Mount Saint Mary College. Gangi may be reached at jane.gangi AT msmc.edu; Benfer at nb6221 AT my.msmc.edu.