In this series, Tu Books Publisher Stacy Whitman shares advice for aspiring authors, especially those considering submitting to our New Visions Award.

Last week on the blog, I talked about hooking the reader early and ways to write so you have that “zing” that captivates from the very beginning. This week, I wanted to go into more detail about the story and plot itself. When teaching at writing conferences, my first question to the audience is this:

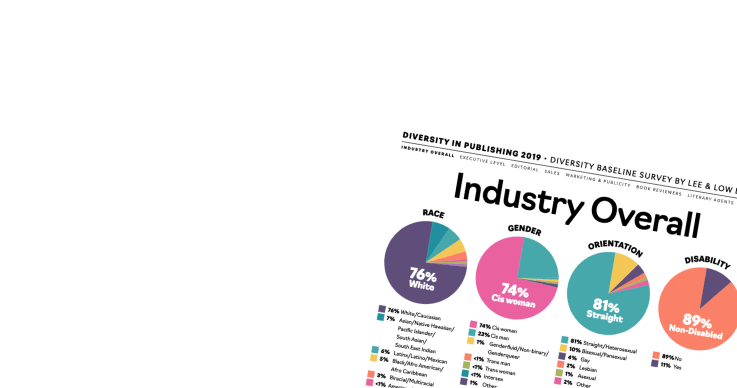

What is the most important thing about a multicultural book?

I let the audience respond for a little while, and many people have really good answers: getting the culture right, authenticity, understanding the character… these are all important things in diverse books.

But I think that the most important part of a diverse novel is the same thing that’s the most important thing about any novel: a good story. All of the other components of getting diversity right won’t matter if you don’t have a good story! And getting those details wrong affects how good the story is for me and for many readers.

So as we continue our series discussing things to keep in mind as you polish your New Visions Award manuscripts, let’s move the discussion on to how to write a good story, beyond just following the directions and getting a good hook in your first few pages. This week, we’ll focus on refining plot.

Here are a few of the kinds of comments readers might make if your plot isn’t quite there yet:

- Part of story came out of nowhere (couldn’t see connection)

- Too confusing

- Confusing backstory

- Plot not set up well enough in first 3 chapters

- Bizarre plot

- Confusing plot—jumped around too much

- underdeveloped plot

- Too complicated

- Excessive detail/hard to keep track

- Too hard to follow, not sure what world characters are in

We’ll look at pacing issues too, as they’re often related:

- Chapters way too long

- Pacing too slow (so slow hard to see where story is going)

- Nothing gripped me

- Too predictable

Getting your plot and pacing right is a complicated matter. Just being able to see whether something is dragging too long or getting too convoluted can be hard when you’re talking about anywhere from fifty to a hundred thousand words, all in one long file. Entire books have been written on how to plot a good science fiction and fantasy book. More books have been written on how to plot a good mystery. If you need more in-depth work on this topic, refer to them (see the list at the end of this post).

Getting your plot and pacing right is a complicated matter. Just being able to see whether something is dragging too long or getting too convoluted can be hard when you’re talking about anywhere from fifty to a hundred thousand words, all in one long file. Entire books have been written on how to plot a good science fiction and fantasy book. More books have been written on how to plot a good mystery. If you need more in-depth work on this topic, refer to them (see the list at the end of this post).

So we won’t get too in depth here, but let’s cover a few points.

Know your target audience

When you’re writing for children, especially young children (middle grade, chapter books, and below), your plot should be much more linear than a plot for older readers who can hold several threads in their heads at once.

Teens are developmentally ready for more complications—many of them move up to adult novels during this age, after all—but YA as a category is generally simpler on plot structure than adult novels in the same genre. This is not to say the books are simple-minded. Just not as convoluted… usually. (This varies with the book—and how well the author can pull it off. Can you?)

But the difference between middle grade and YA is there for a reason—kids who are 7 or 8 or 9 years old and newly independent readers need plots that challenge them but don’t confuse them. And even adults get confused if so much is going on at once that we can’t keep things straight. Remember what we talked about last time regarding backstory—sometimes we don’t need to know everything all at once. What is the core of your story?

Linear plot

Note that “too complicated” is one of the main complaints of plot-related comments readers had while reading submissions to the last New Visions Award.

Don’t say, “But Writer Smith wrote The Curly-Eared Bunny’s Revenge for middle graders and it had TEN plot threads going at once!” Writer Smith may have done it successfully, but in general, there shouldn’t be more than one main plot and a small handful of subplots happening in a stand-alone novel for middle-grade readers.

If you intend your book to be the first in a series of seven or ten or a hundred books, you might have seeds in mind you’d like to plant for book seventy-two. Unless you’re contracted to write a hundred books, though, the phrase here to remember is stand-alone with series potential. Even Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone was pretty straightforward in its plotting—hinting at backstory, but not dumping backstory on readers in book one; setting the stage for potential conflicts down the road but not introducing them beforetime. Book 1 of Harry Potter really could have just stood on its own and never gone on to book 2. It wouldn’t have been nearly as satisfying as having the full 7-book arc, but note how seamlessly details were woven in, not calling attention to themselves even though they’re setting the stage for something later. Everything serves the linear plot of the main arc of book 1’s story. We only realize later that those details were doing double duty.

Thus, when you’re writing for children and young adults, remember that a linear main plot is your priority, and that anything in the story that is not serving the main plot is up on the chopping block, only to be saved if it proves its service to the main plot is true. Plotting affects pace

Plotting affects pace

In genre fiction for young readers, pacing is always an issue. Pacing can get bogged down by too many subplots—the reader gets annoyed or bored when it takes forever to get back to the main thrust of the story when you’re wandering in the byways of the world you created.

Fantasy readers love worldbuilding (to be covered in another post), but when writing for young readers, make sure that worldbuilding serves as much to move the plot forward as to simply show off some cool worldbuilding. Keep it moving along.

Character affects plot

This was not a complaint from the last New Visions Award, but another thing to keep in mind when plotting is that as your rising action brings your character into new complications, the character’s personality will affect his or her choices—which will affect which direction the plot moves. We’ll discuss characterization more another day, but just keep in mind that the plot is dependent upon the choices of your characters and the people around them (whether antagonists or otherwise). Even in a plot that revolves around a force of nature (tornado stories, for example), who the character is (or is becoming) will determine whether the plot goes in one direction or another.

Find an organizational method that works for you

This is not a craft recommendation so much as a tool. Plotting a novel can get overwhelming. You need a method of keeping track of who is going where when, and why. There are multiple methods for doing this.

Scrivener doesn’t work for all writers, so it might not be your thing, but I recommend trying out its corkboard feature, which allows you to connect summaries of plot points on a virtual corkboard to chapters in your book. If you need to move a plot point, the chapter travels along for the ride.

An old-fashioned corkboard where you can note plot points and move them around might be just as easy as entering them in Scrivener, if you like the more tactile approach.

Another handy tool is Cheryl Klein’s Plot Checklist, which has a similar purpose: it makes the writer think about the reason each plot point is in the story, and whether those points serve the greater story.

Whether you use a physical corkboard, a white board, Scrivener, or a form of outlining, getting the plot points into a form where you can see everything happening at once can help you to see where things are getting gummed up.

Further resources

This post is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to plotting a book. Here are some books and essays that will be of use to the writer seeking to fix his or her plot problems. (Note that some of these resources will be more useful to some writers than others, and vice versa. Find what works for you.)

- “Muddles, Morals, and Making It Through: Or Plots and Popularity,” by Cheryl Klein in her book of essays on writing and revising, Second Sight.

- In the same book by Cheryl Klein, “Quartet: Plot” and her plot checklist.

- The Plot Whisperer by Martha Alderson

- I haven’t had experience with this resource, but writer friends suggest the 7-point plot ideas of Larry Brooks, which is covered both in a blog series and in his books

And remember!

Further Reading:

New Visions Award: What NOT to Do

Ask an Editor: Hooking the Reader Early

Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse science fiction and fantasy for middle grade and young adult readers.

Stacy Whitman is Editorial Director and Publisher of Tu Books, an imprint of LEE & LOW BOOKS that publishes diverse science fiction and fantasy for middle grade and young adult readers.