By Jerry Michel, Principal, Willard School-Evanston

Over the past two decades, the growth in our ability to communicate in new and dynamic ways has been nothing short of astounding. Each classroom, office, and home connected to the Internet has global reach, placing a new premium on learning to collaborate across cultures. The amount of information we share on a daily basis is growing exponentially, ever redefining what it means to be up-to-date.

Is the content of our conversations growing as rapidly? What do racism, prejudice, and the educational experiences of minority students look like in the United States today? Although we can celebrate the many victories that have shaped our fight against discrimination, we still live in cities, towns, communities, and neighborhoods that are segregated by both race and opportunity. Schools will be at the forefront of our continuing progress; our ability to be candid and thoughtful when classroom conversations turn to the role racism plays—past and present, overt and covert—will fuel our growth as individuals and as a society.

This struggle is no longer merely a moral one either. Our students’ future success will depend on their ability to work with a wide range of people with diverse background experiences. Realizing our dreams for learning, living, and working in a world shaped by economies without borders will be a daunting task if we assume our work to diminish the influence of racism is largely done.

In a speech commemorating the one-hundredth anniversary of the NAACP, President Barack Obama cautioned those who might think discrimination is no longer an issue. He noted that “the most difficult barriers include structural inequalities that our nation’s legacy of discrimination has left behind; inequalities still plaguing too many communities and too often the object of national neglect.”

Advances in media and technology provide students with tools and opportunities for dynamic interaction with information, imagery, and culture from around the world. Do these advances provide the impetus needed to face the prejudice and discrimination in our midst? As our classrooms and communities become increasingly diverse, so must our strategies for teaching, learning, and living in a global society.

If our students are to succeed as citizens in the twenty-first century, we must help them move beyond tolerance to build foundations for true acceptance. To achieve this, we must build on our students’ background experiences, learn about the cultures in our communities, develop our understanding of the inequities institutionalized in our society, and embrace the strength diversity brings to our classrooms, communities, and nation.

- Facing Our Reluctance to Discuss RaceThink back to a fond memory of one of your teachers. When you remember her or him, do you sense that your teacher was as actively involved in learning as she or he wanted you to be? This is the first step to engaging others in learning: we must be actively and visibly engaged in our own learning.Discussing race is often uncomfortable for adults, especially in a racially mixed setting. Whether it is fear of being insensitive, a lack of understanding or experience, or general avoidance, meaningful discussions concerning race are often hard to come by, especially in the classroom.Before starting discussions about race with your students, examine your own experiences with race as a child, student, teacher, and adult. If you are white, consider Jeane Copenhaver-Johnson’s (2006) observation that race “is not on the radar of many white parents and teachers because whiteness is so rarely scrutinized. That is, those who live with daily privilege often find difficulty recognizing and acknowledging its presence in their daily lives.”

As adults and teachers, we have to be honest with ourselves before we can have honest discussions with others, especially students. Are you willing to make your own struggles and discomfort accessible to your students? When you are unfamiliar with or unaware of the characteristics, traditions, and practices of a culture or an ethnic group, how do you go about understanding your students’ approaches to learning? Examining how your personal beliefs influence your teaching is a powerful tool in combating the tendency to “rely on our own personal experiences to make sense of students’ lives—an unreflective habit that often results in misinterpretations of those students’ experiences and leads to miscommunication.” (Villegas and Lucas, 2007)

- Sometimes It Isn’t What We Say, It’s What We Don’t Say.When speaking about race to children, parents and teachers often avoid potential discomfort by reducing the situation to a nonissue or changing the topic. We downplay our differences by seeking out similarities that, on a simple semantic surface, seem to be perfectly reasonable. The aphorism “we’re all the same on the inside” will be familiar to anyone who has spent time in a primary classroom.While this observation makes it easier for members of the majority, glossing over others’ unique cultural and racial characteristics does little to recognize the contributions members of minority groups make to our society. Race is a social and cultural construct, not a biological predetermination. The experiences we have growing up in any culture indelibly and distinctly make us who we are. If we do not discuss our differences and what makes each culture unique, our silence implies, at best, a lack of awareness or genuine interest. At worst, silence implies a lack of respect.How would your own learning progress if the lessons you worked on in class and the books for children you read from never represented your family’s culture or heritage? If your culture were consistently ignored, how would it affect your learning? Your motivation? Your confidence?

- Let Children Lead the Way. . . .Do not underestimate students’ capacity to discuss race. Students are often more comfortable discussing ethnicity and identity than adults, mainly because students are likely to have friendships and relationships with classmates whose backgrounds reflect a wider range of race and national origin. In the classroom, our job as educators is to provide safe parameters and structures that encourage mutual respect and honest exploration of issues.

Although children may not have the vocabulary to identify the sources and effects of racial tension, they are nonetheless highly aware of the stereotypes present in our society. By providing a supportive setting for students to address issues of race, we acknowledge the obstacles children of color may be facing alone or only with the support of family.Isabella, a fifth grader, faces challenges that are all too familiar today. She remembered being one of the best readers in her class as a kindergartner in Colombia. While others were just learning to read, she was reading “big, thick chapter books.” In the United States, however, reading was a different story for Isabella. Although she successfully completed a program for English-language learners, questions about her reading comprehension lingered year after year. By the time she reached fifth grade, she had repeated a remedial-reading program three times. She no longer read the big, thick chapter books, not even at home. Her early successes were not part of the picture anymore; sadly, they were never in the picture. Her teachers did not know.

Although children may not have the vocabulary to identify the sources and effects of racial tension, they are nonetheless highly aware of the stereotypes present in our society. By providing a supportive setting for students to address issues of race, we acknowledge the obstacles children of color may be facing alone or only with the support of family.Isabella, a fifth grader, faces challenges that are all too familiar today. She remembered being one of the best readers in her class as a kindergartner in Colombia. While others were just learning to read, she was reading “big, thick chapter books.” In the United States, however, reading was a different story for Isabella. Although she successfully completed a program for English-language learners, questions about her reading comprehension lingered year after year. By the time she reached fifth grade, she had repeated a remedial-reading program three times. She no longer read the big, thick chapter books, not even at home. Her early successes were not part of the picture anymore; sadly, they were never in the picture. Her teachers did not know.

“Even my stepfather would give me these baby books at home to read to everybody,” she lamented. “He’d have me read them aloud and say how great I was doing, but I knew they were baby books. Eventually, I just believed everyone that I wasn’t a good reader.”

The fact that the remedial-reading program Isabella repeated three times was really designed to be a one-year intervention certainly didn’t help. The cycle of low expectations continued for Isabella until teachers took the time to learn more about her background experiences. Recalling her strengths as a kindergartner helped boost Isabella’s confidence so that she eventually made great gains over the course of a single school year.

Personal engagement with our students and their cultures will help us find ways to meaningfully connect their background experiences to their classroom lessons. One way to open the door to conversations about race and culture is to plan interactive read-alouds. Finding titles that reflect the diversity of our neighborhoods and nation is the first step. Being aware of students’ family histories, cultural backgrounds and strengths, and the concerns immigrant and minority families have about American schools can help prepare teachers for uncharted and sometimes uncomfortable territory.

When locating and reading selections, focus on: * finding high-quality fiction and nonfiction that is compelling, pertinent, and engaging. Don’t bring in inauthentic texts merely to fill a quota or requirement. * encouraging students to respond to passages as you read. Students are more likely to give genuine reactions and ask questions while listening to a provocative read-aloud selection. * reading and reflecting on reading selections in advance of classroom sessions, preferably with colleagues and friends. * sharing the book with parents or community members whose culture is represented in the book if you have concerns about students’ questions and comments that the reading might evoke. Does the book portray their culture accurately, sensitively, and informatively? How would members of the group portrayed answer the questions you anticipate? * in older grades, letting students preview the reading selection. Give them a day or two to develop and submit their initial reactions. This input will help you prepare responses to potential questions or comments in advance.

- Listen Before You Leap.

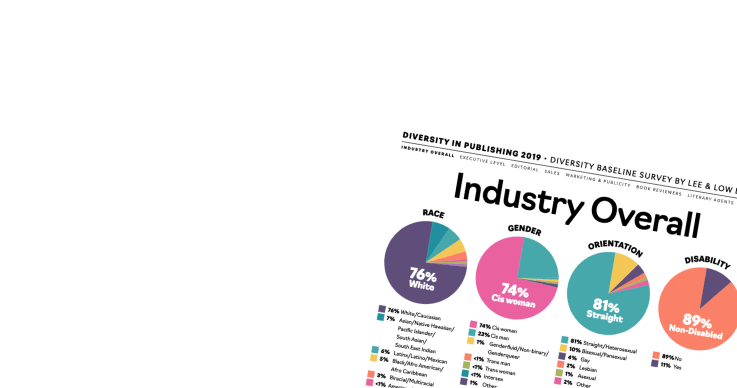

Our definitions of race are rooted in the sum total of our experiences. Our personal, familial, and cultural memories shape our opinions about our own cultural group. Citing data collected by the National Center for Education Statistics, Gary Howard (2007) notes that “ninety percent of U.S. public school teachers are white; most grew up and attended school in middle-class, English-speaking, predominantly white communities and received their teacher preparation in predominantly white colleges and universities.” When working with students whose heritage differs from their own, educators often lack the understanding and strategies that would help them incorporate students’ background experiences, belief structures, and cultural traditions into lessons, activities, and curricula.Students are quick to recognize adults’ lack of awareness. Keri, an eighth grader with a multiethnic set of friends, laughs when she talks about the reactions teachers have when they overhear students’ hallway banter in school. “I don’t know about you,” she explains, “but in the group of friends that I hang out with, a lot of our ‘inside’ jokes are misunderstood.”To an adult, these inside jokes about race, culture, and faith are often offensive; and our first reaction is nearly always one of discomfort. Educators who are able to corral their initial disapproval can create a powerful learning opportunity. Teachers who take the time to understand the context and intent behind what students say are better able to engage in meaningful conversations with their students.Keri continues, “People often come to conclusions about my group of friends ‘harming’ me, most likely because of how sensitive our society is with talking about race. My friends and I are somewhat comfortable talking about race, so as a result, staff and other students sometimes stop and stare. They are shocked by what they hear only because they jump to conclusions. We are all guilty of being defensive when the subject of race comes up, but why is that?”In school, just as in society, students often define who they are by the groups to which they belong. Membership in a group can covey pride and security, both of which are difficult to relinquish. When schools are governed by a dominant culture, fitting in and “finding all the ways that we are alike” can potentially diminish the contributions a diverse student body can bring to classroom lessons.

Students growing up today have many experiences in a multiethnic and multiracial society, from more inclusive media and advertising to the changing demographics of our schools and neighborhoods. In television, multicultural books, and all sorts of media, images featuring the faces and feelings of many cultures are becoming more commonplace. Students accept this as the norm; anything less would be inauthentic. We need to provide them with the encouragement and faith that they will be the ones to champion causes that will make our society more accepting of the diversity of cultures that make up our individual communities, countries, and world.

Classroom conversations and activities that build a climate of acceptance should: * focus on listening to students’ ideas and the reasons behind them. * emphasize that it is the responsibility of both majority and minority groups to address issues of race. * allow adequate time for students to process questions before giving responses. Teachers typically do not wait more than a second or two when calling on students; extending the “wait time” between question and answer encourages more thoughtful responses and communicates respect for ideas. Do not cut students short when their first responses do not seem to make sense; that which is initially unclear may end up being insightful. * express confidence in students’ abilities to provide leadership and solutions to the struggle against racism, especially when adults’ efforts stall.

- Confront Stereotyping When It Occurs.

In any school hallway or playground, it doesn’t take long before you hear the influence of stereotypes in name-calling, taunting, and hallway banter. Muslim students are called terrorists. Speech patterns of minority groups are exaggerated or mocked. African American and Latino youth are associated with gangs and gang culture, even in communities in which gangs are not prevalent. Stereotyping in this way is hurtful and discriminatory, yet students may not have the experience or resources to understand fully the impact of the words they are using and hearing.When students’ conversations or language reflect racist stereotypes, listen first for intent. Are they friends, enemies, or “frenemies”? Don’t assume that younger students know the emotional weight behind the words they use. Ask them: * to explain the words or term they chose to use. * what the words mean to them. * what they think the words mean to others. * why they chose to use the words they did.There are two reasons for asking these questions. First, students’ answers give teachers and parents a more complete picture of a child’s understanding of the situation. Second, the question-and-answer period provides time for the situation to de-escalate. It is important to consider the power of social momentum in school groups; ideas can take hold quickly, and students will repeat language and behavior without pausing to reflect on the meaning or influence their actions carry. Since racial intolerance, bias, and stereotyping are learned behaviors, the time we spend providing students with thoughtful alternatives is crucial. Students need the time and tools to evaluate the consequences of their actions, both for themselves and others.It isn’t enough simply to discuss stereotyping. By being honest, direct, and forthcoming, we can use these teachable moments to help students unlearn the negative behaviors they have developed. When students can identify why their actions are troubling to others (rather than identify their actions as something that gets them into trouble), they are ready to take the first steps toward having honest discussions about race. - Don’t Wait for Heritage Days and History Months.

Growing up, much of our exposure to racial and ethnic groups other than our own is through the food featured at cultural celebrations. In planning curriculum and school events, it is important to understand that by waiting for a special day, month, or celebration to discuss and explore issues of race, we silently assert the dominance of the majority culture. Copenhaver-Johnson (2006) astutely crystallizes researchers’ findings that “white teachers tend to view progressive curricular choices as culture-free.” In other words, we can’t embrace diversity while homogenizing the lessons we write and the materials we use.As many African American educators, researchers, and students point out, if February is Black History Month, what does that make the other eleven months?Promoting a more inclusive classroom climate can begin with a more diverse classroom library. Look beyond books about the Holocaust, escapes from slavery, and crossing a border. Look for books that celebrate everyday life, where the story is central to young readers’ enjoyment and understanding. Look for books for children that celebrate relatively unknown heroes of all backgrounds. When the titles we select for the library reflect the broader communities we serve, we provide more than literacy development; we honor our students’ families and cultures. - Embrace the Long Haul: Actions, Not Words, Lead to Change.

Children and young adults have always been impatient. Cell phones, laptop computers, and other media tools make our access to information portable and almost instantaneous. Most people today cannot imagine taking a trip without using online mapping, a GPS device, or a smart-phone application that directs them turn by turn from origin point to destination. Having instant access to information may make us feel as if we are more aware, but some understandings can only be uncovered through long journeys and self-discovery. Each generation has greater access to the knowledge from previous generations; each generation discovers that it takes time to develop the wisdom to use this knowledge well.Taking a good idea from inception to reality can seem to take an eternity. The institutions that perpetuate racism, both knowingly and unwittingly, have been in place for a long time. Classroom conversations and literacy instruction are important tools for combating racism, but it is our actions as students, teachers, and community leaders that will make the difference. Do not judge your success by the effectiveness of a single lesson. Judge your success by the slow and steady change you make over the course of years. Each year ask yourself, “What can I do better? How can I better help students move from conversations about tolerance to actions that promote acceptance?” The influence we can have as individuals is enhanced by our ability to interact meaningfully with communities around the world. Don’t wait for a pen pal project or an exchange activity to start thinking about what it means to be a participant in the global community. Start sharing articles, news, and stories from around the world with students as part of your regular read-aloud time or when you discuss current events. Always be on the lookout for opportunities to make connections between the books you read, themes you explore, and what is happening in the world around us.

Beyond Tolerance: Expecting Acceptance

No matter how dedicated and persistent we are, helping students, classes, schools, and districts face individual and institutional racism is not a job we can do alone or without the input of others. The following resources provide additional in-depth discussion, specific ideas and lessons to pursue, solid research on immigrants’ experiences entering American schools, and links to online resources. Use them to generate faculty discussions, remembering that educating others begins with educating ourselves. Advocate change, promote hope, and focus on changing one heart and mind at a time.

Jerry Michel is a Principal at Willard School-Evanston/Skokie District 65 in Evanston, Illinois, just outside of Chicago. He has been involved in literacy education and professional development for over fifteen years as an elementary school teacher, administrator, and consultant.

References

Copenhaver-Johnson, Jeane. “Talking to Children About Race: The Importance of Inviting Difficult Conversations.” Childhood Education (Fall 2006): 12–20.

Howard, Gary. “As Diversity Grows, So Must We.” Educational Leadership. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (2007): 64(6).

Sloan, Willona M. “Creating Global Classrooms.” Education Update. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (2009): 51(1).

Southern Poverty Law Center, Teaching Tolerance Project: www.tolerance.org

Suaréz-Orozco, Carola, Marcello M. Suaréz-Orozco, and Irina Todorova. Learning in a New Land: Immigrant Students in American Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Villegas, Ana María, and Tamara Lucas. “The Culturally Responsive Teacher.” Educational Leadership. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (2007): 64(6).