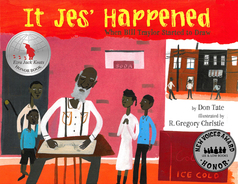

TEACHER'S GUIDE FOR:

It Jes’ Happened

By Don Tate

Illustrations by R. Gregory Christie

Synopsis

Growing up as an enslaved boy on an Alabama cotton farm, Bill Traylor worked all day in the hot fields. When slavery ended, Bill’s family stayed on the farm as sharecroppers. There Bill grew to manhood, raised his own family, and cared for the land and his animals.

By 1935 Bill was eighty-one and all alone on his farm. So he packed his bag and moved to Montgomery, the capital of Alabama. Lonely and poor, he wandered the busy downtown streets. But deep within himself Bill had a reservoir of memories of working and living on the land, and soon those memories blossomed into pictures. Bill began to draw people, places, and animals from his earlier life, as well as scenes of the city around him.

A young artist, Charles Shannon, admired Bill’s work, and in 1939 began supporting Bill with art supplies. Bill earned a few cents for his work every now and then, but continued to draw from his spot on the street for the pure joy of creating images that gave him pleasure. Charles arranged for an exhibit of Bill’s work at the New South art gallery on February 12, 1940, to share Bill’s images of his memories and experiences with the world.

Today Bill Traylor is considered to be one of the most important self-taught American folk artists. It Jes Happened, winner of Lee & Low’s New Voices Award Honor, is a lively tribute to a man who has enriched the world with more than twelve hundred warm, energetic, and often humorous pictures.

BACKGROUND

Author’s Note: This story is true to the facts of Bill Traylor’s life and the times during which he lived, although there are discrepancies among sources about some dates and aspects of his life. In crafting this biography, the author relied on the most authentic sources available, his knowledge of the communities in which Traylor lived, and the realities of society at the time. The quote “It jes’ come to me” on Page 5 has long been linked to Bill Traylor, said to be a response he gave when a reporter, Allen Rankin, asked Traylor why he began to draw. Charles Shannon, Traylor’s friend and supporter, later said Traylor never replied to the question and that Rankin put the words in Traylor’s mouth, adapting them from something Shannon himself had said to Rankin.

Afterword: It was reported that when Bill Traylor visited the exhibit of his work at the New South art gallery, he walked around the room and occasionally commented on the artwork as though he had never seen any of it before. After Traylor returned to North Lawrence Street, he never mentioned the exhibition again.

Charles Shannon (1914–1996) was born in Montgomery, Alabama. He studied at the Cleveland School of Art, and while there he became interested in painting the culture of the South, especially that of African Americans. After moving back to Alabama, Shannon met Bill Traylor in 1939, and within a couple of weeks began bringing him art supplies. Over the next three years Traylor created somewhere between 1,200 and 1,500 drawings and paintings. Shannon continued to support Traylor by purchasing many of his works.

Shannon arranged for a second exhibit of Traylor’s drawings at the Fieldston School of the Ethical Culture of Riverdale, New York, in January 1942. The Museum of Modern Art in New York City attempted to purchase sixteen drawings from the exhibition, but Shannon rejected the museum’s offer of only one or two dollars per piece.

In June 1942 Shannon was drafted into the military, where he served until 1946. During that time Traylor drifted among the homes of various relatives throughout the country. The rheumatism in his left leg became worse, which led to gangrene and then amputation. After his wound healed, Traylor went back to his spot on North Lawrence Street.

By the time Shannon returned to Montgomery, Traylor’s health had deteriorated even more. Traylor had left his place on the street and was living with one of his daughters in another part of the city. Disheartened and uninspired, Traylor continued to draw, but his pictures lost their spark. He died in October 1949 at the age of ninety-five.

For many years Charles Shannon kept Bill Traylor’s art in storage because of a lack of public interest. By the late 1970s Shannon decided it was time to share Traylor’s drawings with the art world again. As a result, in 1982 Traylor’s work was exhibited at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. The exhibition, entitled Black Folk Art in America 1930–1980, included thirty-six of Traylor’s pictures and led to wide recognition of his work. Since then Bill Traylor has come to be regarded as one of the most important self-taught American folk artists of the twentieth century. His pictures are also considered to be “outsider art,” work created by a person without formal training who lives on the edge of established culture and society and works outside the mainstream art world of schools, galleries, and museums.

Exactly why Bill Traylor started to draw remains a mystery. Perhaps the ability to draw was within him his entire life, surfacing when circumstances made it possible. Whatever the reason, on a city sidewalk far away from his rural home, Bill Traylor re-created his life with imagination, humor, and engaging simplicity.

Folk vs. Outsider vs. Mainstream Art: “Folk art” and “outsider art” are labels applied to the work of self-taught artists. Art critic Roger Cardinal coined the term “outsider art” in the early 1970s to describe artists who had little to no professional training in technique or art historical traditions. The term “outside art” has also been applied to and included art by adults in prison or mental institutions, and even children. Art created outside the art establishment and training developed popularity starting in the 1920s even though people had been creating works before that time. Outsider art, like Bill Traylor’s, is often spontaneous, unaltered, and instinctive to the creator. Mainstream artists, museums, or galleries unfortunately often only recognize and accept outsider art after the artist’s death. Folk art is a specific sub-category of outsider art. In folk art, ordinary people, indigenous people, or others draw inspiration from their surroundings, everyday routines, and lived experiences. Folk art reflects their traditions, communities, and cultures. Art materials for such works are typically used everyday, such as fabric, wood, and metal.

For a historical timeline of folk and outsider art, check out The Anthony Petullo Art Collection and TAUNY’s “What is Folk Art?” The only international journal of outsider art, Raw Vision, attempts to bring attention to past and current artists. Bill Traylor’s art is on display at Just Folk gallery in Santa Barbara, California, which houses a collection of American folk and outsider art.

Great Depression in the South: Beginning in the early twentieth century, an insect called the boll weevil infested the agricultural South, including Alabama. The pest targeted cotton, the central cash crop of the region, and thereby devastated the regional economy. For more information on the boll weevil and its impact, check out the Encyclopedia of Alabama. By the time the Great Depression struck in 1929, the rural South had already been experiencing low wages, low crop prices, and reduced crop output for more than a decade. While there were a few large landowners, most (African American and white) people were tenant farmers, factory workers, or sharecroppers. According to the Library of Congress, “no group was harder hit than African Americans. By 1932, approximately half of black Americans were out of work.” President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal Program offered some assistance to struggling families by the late 1930s, but the United States entry into WWII had the biggest impact in creating jobs.

Sharecropping: After the Civil War and during Reconstruction, a new labor system of sharing labor and land developed, called sharecropping. Slavery had been a central element of the Southern economy and former masters attempted to retain power over the people they had formerly enslaved, even as the newly freed African Americans demanded wages. Many large landowners, fearing a loss of profits and labor, coerced freed black people into signing unfair labor contracts and subjected them to violence to control them. Landowners “allowed” tenants, or sharecroppers, to use their land in return for a share of the crops produced. Sharecroppers became tied to the land because unpredictable harvests and extra charges left many in debt. Most sharecroppers never saw actual currency because most transactions involved the crops. For excellent primary sources about this period, check out PBS’s “Slave to Sharecropper,” and more explanation about the sharecropping system can be found at PBS’s “Slavery by Another Name: Sharecropping.”

The Great Migration: Between 1915 and 1970, more than six million African Americans left the South for cities across the country. Due to economic depression and social injustice in the South, African Americans sought the Northeast, Midwest, and West Coast for new opportunities. Many factors influenced African American migration during this period. The boll weevil’s destruction of cotton and the bleak prospects of sharecropping were huge motivating factors. According to PBS’s “The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow: The Great Depression Chapter,” “cotton prices plunged from eighteen cents to six cents a pound.” Additionally, political and social oppression in the South led many to believe that the North would offer more tolerance and greater freedoms in education and home ownership. Violence in Southern states increased in the early twentieth century with more lynchings, the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, and voter disenfranchisement. Finally, WWII had a tremendous impact on manufacturing and the creation of new jobs. The Great Migration transformed American demographics. Read and listen to NPR’s “Great Migration: The African-American Exodus North.” More information on the impact of the Great Migration, specifically in Alabama, can be found at the Encyclopedia of Alabama.

BEFORE READING

Prereading Focus Questions

(Reading Standards, Craft & Structure, Strand 5 and Integration of Knowledge & Ideas, Strand 7)

Before introducing this book to students, you may wish to develop background and promote anticipation by posing questions such as the following:

1. Take a look at the front and back cover. Take a picture walk. Ask students to make a prediction. Do you think this book will be fiction or nonfiction? What makes you think so? What clues do the author and illustrator give to help you know whether this book will be fiction or nonfiction?

2. What do you know about stories that are biographies? What kinds of things happen in biographies? What are some things that will not happen in biographies? Why do authors write biographies? How do you think their reasons differ from authors who write fiction? What are some of the characteristics of a biography?

3. What does an artist do? What are some different types of art with which you are familiar? Why do people make are? Why do people like art? Share a memory you have of going to an art museum, a favorite piece of art, or a piece of art you made.

4. What do you know about farming? What kinds of things do farmers grow? What challenges do farmers face?

5. What do you know about economic conditions during the 1930s in the United States? What were some problems people faced? Why might people have left their farmland to move to a city?

6. Why do you think I chose this book for us to read today?

Exploring the Book

(Reading Standards, Craft & Structure, Strand 5, Key Ideas & Details, Strand 1, and Integration of Knowledge & Ideas, Strand 7)

Read and talk about the title of the book. Ask students what they think the title means. Then ask them what they think this book will most likely be about and who the book might be about. What places might be talked about in the text? What do you think might happen? What information do you think you might learn? What makes you think that?

Take students on a book walk and draw attention to the following parts of the book: front and back covers; title page; acknowledgments, author’s note, sources; illustrations; and backmatter (afterword) with images.

Setting a Purpose for Reading

(Reading Standards, Key Ideas & Details, Strands 1–3)

Have students read to find out who Bill Traylor was, what he did, and why he is important. Encourage students to consider why the author, Don Tate, would want to share this story with children.

Have students also read to determine how the text is structured and how the information is presented.

VOCABULARY

(Language Standards, Vocabulary Acquisition & Use, Strands 4–6)

The story contains several content-specific and academic words and phrases that may be unfamiliar to students. Based on students’ prior knowledge, review some or all of the vocabulary below. Encourage a variety of strategies to support students’ vocabulary acquisition: look up and record word definitions from a dictionary, write the meaning of the word or phrase in their own words, draw a picture of the meaning of the word, create a specific action for each word, list synonyms and antonyms, and write a meaningful sentence that demonstrates the definition of the word.

CONTENT SPECIFIC

cotton slaves/enslaved steamboats Civil War sharecroppers

cabin plow fiddle rheumatism joints

art studio canvases exhibit art gallery horse-drawn buggies

ACADEMIC

elderly discarded fetching profits equipment scarce

brood amused personalities scattered eventually wandered

bustled rumbled befriended pallet employment storage

folks admirers talkative intrigued humorous motivation

festivities automobiles homeless caskets loneliness steady

AFTER READING

Discussion Questions

After students have read the book, use these or similar questions to generate discussion, enhance comprehension, and develop appreciation for the content. Encourage students to refer to passages and illustrations in the book to support their responses. To build skills in close reading of a text, students should cite evidence with their answers.

Literal Comprehension

(Reading Standards, Key Ideas & Details, Strands 1 and 3)

1. Who is the elderly man we meet on the first page of the book? What is he doing?

2. Where did Bill Traylor get his name?

3. What did Bill like to do as a boy?

4. What happened to the Traylor farm and Bill’s family after the Civil War? How did Bill respond to these events?

5. By 1881, what was happening in Bill’s life?

6. How did Bill feel about money?

7. Why did Bill leave his farm and move to Montgomery? How old was he when he moved?

8. What were some jobs Bill had in Montgomery?

9. How did he become homeless? Where did he sleep at night?

10. At what age did Bill Traylor start to draw? What motivated him to start drawing? Where did he draw?

11. Who was Charles Shannon? Why was he an important person in Bill Traylor’s life? What did Charles do for Bill?

12. How do you think Bill felt about Charles? How do you know?

13. What kinds of things did Bill say about his drawings?

14. How did visitors respond to Bill Traylor’s work in the gallery? How did Bill respond?

Extension/Higher Level Thinking

(Reading Standards, Key Ideas & Details, Strand 2 and 3 and Craft & Structure, Strand 6)

1. What do you call two words that sound the same but have different meanings? (homophones) The author uses two of these words in the text: pallet and palette? What does each word mean? How do you know?

2. How did Bill Traylor’s circumstances change from his boyhood to his adulthood? What events in history affected the events in his life?

3. At the end of the Civil War, what choice did Bill’s family make? Why do you think they chose to stay in the area where they once were enslaved? How did that choice shape their lives?

4. What were Bill’s favorite animals on his farm? How does he describe them? How does he give each animal human characteristics?

5. What did the author, Don Tate, mean when he says, “the women sang up a storm”?

6. What did Bill mean when he says, “My white folks had died and my children scattered”? How do you think Bill felt at this time?

7. Why might Bill’s children have left the farm once they grew up?

8. What challenges did Bill face in Montgomery? How were these challenges different from the challenges he faced on the Traylors’ farm?

9. How did not being able to read or write affect Bill in Montgomery?

10. Why do you think the owners of the Ross-Clayton Funeral Home offered Bill a place to sleep?

11. What did Bill Traylor do with all the memories he saved up? What memories were important to Bill? How do you know?

12. Why do you think Bill Traylor shared his memories through art?

13. How did people react to Bill’s drawings? How do you know?

14. What did the author mean when he says Bill Traylor’s pictures “danced with rhythm”?

15. Why do you think Bill decided to draw and paint what he did? What events did he draw/paint from his past? What things did he draw/paint from his present?

16. Why do you think Bill preferred a “spare” palette?

17. How did Bill feel when people bought his work? Why did he think it was funny someone would buy art, especially his art?

18. How are the illustrator’s paintings similar to Bill Traylor’s? Why do you think the illustrator drew and painted his pictures this way?

19. Why do you think Charles Shannon admired Bill Traylor’s art? Why did Charles Shannon buy Bill art supplies?

20. What made Bill Traylor’s art unique?

21. What kind of person was Bill Traylor? How would you describe him? What motivated him? What character traits did he show? Think about what he said and what he did. Does the author want you to aspire to be like Bill Traylor the artist or not? What makes you think so?

22. What is the theme/author’s message of the story? What does the author, Don Tate, want you to learn from Bill Traylor’s experiences?

23. Why do you think it took until 1982 for Bill Traylor’s work to become popular?

24. When Bill Traylor felt lonely, he decided to start drawing. Why do you think that made him feel better?

25. Bill Traylor’s art pieces were worth only a few cents in the 1930s, but now sell for tens of thousands of dollars. Why do you think they have gone up in value so much? (note: not just inflation)

Literature Circles

(Speaking & Listening Standards, Comprehension & Collaboration, Strands 1–3 and Presentation of Knowledge & Ideas, Strands 4–6)

If you use literature circles during reading time, students might find the following suggestions helpful in focusing on the different roles of the group members.

• The Questioner might use questions similar to the ones in the Discussion Question section of this guide.

• The Passage Locator might look for lines in the story that explain new vocabulary words.

• The Illustrator might create scenes on a timeline that follow the major events in Bill Traylor’s life.

• The Connector might find books written about other famous artists and compare and contrast how their work was perceived by others.

• The Summarizer might provide a brief summary of the group’s reading and discussion points for each meeting.

• The Investigator might look for information about slavery, the Civil War, and challenges faced by enslaved people once they were freed after the Civil War.

*There are many resource books available with more information about organizing and implementing literature circles. Three such books you may wish to refer to are: GETTING STARTED WITH LITERATURE CIRCLES by Katherine L. Schlick Noe and Nancy J. Johnson (Christopher-Gordon, 1999), LITERATURE CIRCLES: VOICE AND CHOICE IN BOOK CLUBS AND READING GROUPS by Harvey Daniels (Stenhouse, 2002), and LITERATURE CIRCLES RESOURCE GUIDE by Bonnie Campbell Hill, Katherine L. Schlick Noe, and Nancy J. Johnson (Christopher-Gordon, 2000).

Reader’s Response

(Writing Standards, Text Types & Purposes, Strands 1–3 and Production & Distribution of Writing, Strands 4–6)

(Reading Standards, Key Ideas & Details, Strands 1–3, Craft & Structure, Strands 4–6, and Integration of Knowledge & Ideas, Strands 7–9)

Use the following questions and writing activities to help students practice active reading and personalize their responses to the book. Suggest that students respond in reader’s response journals, essays, or oral discussion. You may also want to set aside time for students to share and discuss their written work.

1. Over the course of his life, Bill Traylor “saved up memories . . . deep inside himself.” What are some memories you have of friends and family that you feel you’d like to save deep inside yourself? What makes these memories important?

2. Read the Afterword. What information about Bill Traylor did you learn that was not in the text? What information about Charles Shannon did you learn that was not in the text? Cite passages from the book to support your answer.

3. How was Bill Traylor’s work received in 1940? How was it received in 1982? Why do you think it took so long for people to change their minds about Bill Traylor’s art?

4. In the book, the illustrator chose to make the illustrations suggest Bill Traylor’s art. Why do you think he made that choice? How did the illustrations help you understand the information presented?

5. Which parts of the book did you connect to the most? Which parts of the story did you connect to the least? Why? What memory can you share of creating art, studying art, or visiting an art museum?

6. When Bill Traylor felt lonely, he started to draw. Why do you think that made him feel better? What do you do when you feel lonely? How might music, writing, dance, singing, and/or drawing help people feel better?

7. Have students write a book recommendation for It Jes’ Happened explaining why they would or would not recommend this book to other students.

ELL Teaching Activities

(Speaking & Listening Standards, Comprehension & Collaboration, Strands 1–3 and Presentation of Knowledge & Ideas, Strands 4–6)

(Language Standards, Vocabulary Acquisition & Use, Strands 4–6)

These strategies might be helpful to use with students who are English Language Learners.

1. Assign ELL students to partner-read the story with strong English readers/speakers. Students can alternate reading between pages, repeat passages after one another, or listen to the more fluent reader.

2. Have each student write three questions about the story. Then let students pair up and discuss the answers to the questions.

3. Depending on students’ level of English proficiency, after the first reading:

• Review the illustrations in order and have students summarize what is happening on each page, first orally, then in writing.

• Have students work in pairs to retell either the plot of the story or key details. Then ask students to write a short summary, synopsis, or opinion about what they have read.

4. Have students give a short talk about what they admire about a character or central figure in the story.

5. The book contains several content-specific and academic words that may be unfamiliar to students. Based on students’ prior knowledge, review some or all of the vocabulary. Expose English Language Learners to multiple vocabulary strategies. Have students make predictions about word meanings, look up and record word definitions from a dictionary, write the meaning of the word or phrase in their own words, draw a picture of the meaning of the word, list synonyms and antonyms, create an action for each word, and write a meaningful sentence that demonstrates the definition of the word.

INTERDISCIPLINARY ACTIVITIES

(Introduction to the Standards, page 7: Student who are college and career ready must be able to build strong content knowledge, value evidence, and use technology and digital media strategically and capably)

Use some of the following activities to help students integrate their reading experiences with other curriculum areas. These can also be used for extension activities, for advanced readers, and for building a home-school connection.

Social Studies

(Reading Standards, Integration of Knowledge & Ideas, Strands 7 and 9)

1. Ask students to research Montgomery, Alabama, in 1939. What did the town look like? What was going on at that time in history? What challenges were African Americans facing? Then discuss how knowing this information helps students understand Bill Traylor’s life and experiences.

2. Have students learn about sharecropping. Why did some formerly enslaved people choose to become sharecroppers? What other choices were available to people after the Civil War? How did sharecropping still give power to the white landowners? What kind of crops did sharecroppers grow in different states in the South?

Science

(Reading Standards, Integration of Knowledge & Ideas, Strands 7 and 9)

Encourage students to investigate the boll weevil. Where did the pest come from? What kinds of crops do boll weevils eat? Why were Southern farms in the early twentieth century so vulnerable to the boll weevil? Does the boll weevil have any predators? How did farmers learn to control or eliminate the boll weevil? How did the boll weevil change farming in the South? Draw the life cycle of the boll weevil and one type of food chain containing the boll weevil.

Art

1. Have students explore Bill Traylor’s drawings. What does he like to draw? What do the people, animals and buildings look like in his work? Where did he get his images? What materials and colors did he prefer to work with? Read and discuss the New York Times review of an exhibit of Bill Traylor’s work.

2. Ask students to pick a memory from their daily lives and draw it in the style of Bill Traylor.

3. Show students two pieces of Bill Traylor’s artwork. Have students compare and contrast the pieces. Show students one piece from Bill Traylor and one piece from Georgia O’Keefe, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Wassily Kandinsky, or Salvador Dali (formal artists painting and creating at the same time as Bill Traylor). Have students compare and contrast the pieces. What materials did the artists use? What scenes were depicted? What mood does each piece convey? Why do you think these works are considered art? (Note: Examples of artworks by all the artists mentioned can be found online on numerous sites.)

4. Have students discuss what they think art is. Lead the discussion by asking students why people at the galleries and museums at first didn’t consider Bill’s work art and wouldn’t pay much attention to it. Why do you think people’s feelings toward his work changed over time? Why does some art go into museums and get purchased for thousands of dollars, but other art doesn’t?

Writing

(Writing Standards, Text Types & Purposes, Strands 1 and 2)

(Language Standards, Knowledge of Language, Strand 3)

1. Ask students to imagine that they are hosting a gallery show of Bill Traylor’s work. Encourage students to write a paragraph persuading other students and people in their town to come view his pieces. Students may also create a postcard or poster advertising the gallery show.

2. It Jes’ Happened is a great book for the study of verbs and word choices. Disappeared, jumped, waved, chuckled, tiptoed, strutted, and slithered are just a few of the verbs used. Have students make a list of all the action verbs in the book. Encourage them to discuss why they think the author, Don Tate, chose a word like strutted instead of walked. Have students use their list in their next writing assignment. Reflect on how strong verbs improve writing and visualization.

Home-School Connection

(Reading Standards, Integration of Knowledge & Ideas, Strands 7 and 9)

(Speaking & Listening Standards, Comprehension & Collaboration, Strands 1–3)

(Writing Standards, Text Types & Purposes, Strand 2 and Research to Build & Present Knowledge, Strand 7)

1. Support students in interviewing their parents, grandparents, or guardians. Was there a time when they felt lonely? What did they do to heal their loneliness? What do they do to share or remember memories? Do they ever use drawing, music, dance, writing, or storytelling to share memories? How does that help them remember or feel better?

2. Bill Traylor did not care if anyone liked or bought his art. In fact, he created his images to help him conquer his loneliness and remember his life experiences. Encourage students to ask their parents, grandparents, or guardians about a time they felt confident. What motivated them? Why is it important to have confidence in something you are doing and enjoy? What advice do they have for when others laugh at or criticize what you are doing?

About This Title

Guided Reading:

SLexile:

830LInterest Level:

Grades 1 - 6Reading Level:

Grades 3 - 4Themes

Nonfiction, United States History, Slavery, Overcoming Obstacles, Imagination, History, Dreams & Aspirations, Childhood Experiences and Memories, African/African American Interest, Biography/Memoir, Art, Empathy/Compassion, Gratitude, Integrity/Honesty , Persistence/Grit, Self Control/Self Regulation

Collections

Pedro Noguera Reluctant Readers Collection , African American Collection English 6PK, African American English Collection Grades 3-6, Black History Collection Grades 3-6, Pedro Noguera Diverse Collection Grades 3-5, Appendix B Diverse Collection Grades 3-6, Black History Month Bestselling Books Collection, Teaching about Slavery Collection, Biography and Memoir Grades 3-6, Nonfiction Grades 3-6, Biography and Memoir Middle School, Art and The Arts Collection , New Voices Award Winners & Honors Collection, Persistence and Determination Collection, African American English Collection Middle School, Juneteenth Webinar Collection, Reconstruction Webinar Collection

Want to know more about us or have specific questions regarding our Teacher's Guides?

Please write us!general@leeandlow.com Terms of Use