TEACHER'S GUIDE FOR:

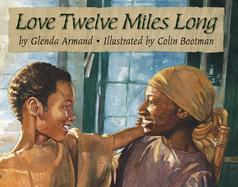

Love Twelve Miles Long

By Glenda Armand

Illustrations by Colin Bootman

View and Download the Teacher's Guide

Synopsis

It’s late at night, and Frederick’s mother has traveled twelve miles to visit him. Frederick Douglass is trying to understand why he can’t live with his mother, who is enslaved on another plantation. When Frederick asks her how she can walk so far, Mama recounts her journey mile by mile and explains that every step of the way is special, as it brings them closer together. Mama answers Frederick’s questions by describing what each mile of her journey is for—remembering, listening, praying, singing, and finally, love. Her strength to travel the distance between them is a poetic testament to the human spirit, showing Frederick that although the road through life is full of hardships, hope, joy, and dreams can grow along the way.

Winner of Lee & Low’s New Voices Award, Love Twelve Miles Long offers a glimpse into a little-known part of Frederick Douglass’s childhood. Set on a plantation in 1820s Maryland, this story based on the life of young Frederick Douglass shows the power of his mother’s love. The faith she has in her son puts him on a path to escape enslavement and to become a noted intellectual, a highly respected champion of human rights, an influential writer and speaker, and an unforgettable leader.

Love Twelve Miles Long is an intergenerational story that highlights the universality of the love between a parent and a child, which can transcend even the most difficult circumstances. The warm and tender exchanges between young Frederick and his mother will appeal to children of all backgrounds who cherish bedtime rituals. Expressive, candlelit paintings illuminate the bond between parent and child in this heartfelt story.

BACKGROUND

From the Afterword: Frederick did gain his freedom, just as his mother had hoped. After escaping from slavery, he changed his last name from Bailey (his mother’s last name) ?to Douglass to make it harder for his former master to find him. Frederick Douglass eventually led other slaves to freedom and became a famous writer and public speaker who spoke out against slavery. He visited the White House several times to speak with President Abraham Lincoln about freedom for those who were enslaved. When slavery finally ended, Douglass joined the fight for the rights of women.

Although Douglass’s mother did not live to see her son become a man, he knew that she would have been proud of him. He said that he owed much of his success to her. Unlike most people who were enslaved, Harriet Bailey, Frederick’s mother, could read. She may have learned the way Douglass did: from members of their master’s family. Harriet Bailey also had a way with words, a gift she passed on to her son, perhaps during those precious nighttime visits. In his autobiography, Douglass wrote that his mother taught him a powerful lesson: that he was not “only a child but somebody’s child.” Her love for him gave Frederick Douglass the confidence to believe that he was not born to be enslaved but was indeed destined to do great things and lead a remarkable life.

<i>Frederick Douglass (1818–1895)</i>: The son of an enslaved woman and an unknown white man, Frederick Augustus Bailey Douglass was born into slavery in Maryland. According to PBS’s Africans in America: Judgment Day, he spent his childhood with his grandparents and an aunt, only seeing his mother infrequently before her death when he was seven. Douglass escaped slavery in Baltimore by 1838 at the age of 20 and became an abolitionist in the North. He befriended and was mentored by William Lloyd Garrison (founder and editor of the Liberator). Douglass published his autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, in 1845 and created the black newspaper, The North Star, in 1847. Many of the speeches, personal correspondence, and notes of this “outspoken antislavery lecturer, writer, and publisher” are available as part of The Frederick Douglass Papers at the Library of Congress. Throughout the Civil War, Douglass advised Abraham Lincoln, recruited northern African Americans for the Union Army (including his own two sons), and fought for equal rights for African Americans. He was popular for his persuasive writing and speeches, and he toured internationally speaking out against racism. After the Civil War, he continued to argue for African American rights and additionally supported women’s rights. Explore more about this historic leader at America’s Story from America’s Library.

<i>Antebellum slavery (prior to the Civil War)</i>: According to The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, between 1500 and 1870, about 500,000 African men, women, and children were brought to the United States and enslaved. Those who were enslaved were treated worse than livestock and sold on auction blocks to white landowners. African American slaves were put to work as carpenters, fence builders, childcare givers, nurses, blacksmiths, farmers, and more, according to “Horrible Experiences Slaves Endure in the 1800s” by University of Richmond’s History Engine Project. Although the United States Congress banned the African slave trade in 1808, slavery in the United States continued and grew because new laws dictated that any child born to an enslaved woman would also be enslaved. There were no rights or protection given to slaves, so white owners could punish, torment, and rape them without consequence. To see the political expansion of slavery, check out the American Anthropological Association’s RACE Project’s “Expansion of Slavery in the U.S.”

African spirituality, traditions, and culture were often lost, but some songs, foods, and beliefs were passed down from generation to generation or mixed with life in the United States. Between state laws and owners’ perspective, most enslaved people were banned from learning to read and write, practicing Christianity, and engaging in traditions from Africa. Those who were enslaved could be bought or sold at will, and marriages and families could be dissolved at any time. They resisted the physical, emotional, and mental degradation of slavery in various ways including escaping, helping others escape, learning to read and write in secret, resisting work, sabotage, practicing religion, passing on news, and engaging in violence. Images of this time period and memories from enslaved people can be found at PBS’s Slavery and the Making of America.

BEFORE READING Pre-reading Focus Questions (Reading Standards, Craft & Structure, Strand 5 and Integration of Knowledge & Ideas, Strand 7)

Before introducing this book to students, you may wish to develop background and promote anticipation by posing questions such as the following:

- Take a look at the front and back covers. Take a picture walk. Ask students to make a prediction. Do you think this book will be fiction or nonfiction? What makes you think so? What clues do the author and illustrator give to help you know whether this book will be fiction or nonfiction?

- What do you know about texts that are based on the lives of famous people? Why do authors write about famous people that have some fictional parts? How do you think their reasons differ from authors who write all fiction or all nonfiction?

- What do you know about slavery in United States history? What do you know about the Underground Railroad and the Civil War? What other books have you read that discuss slavery? Why do you think it is important to learn about this history?

- What do you know about Frederick Douglass? What do you know about Abraham Lincoln? What are some of the challenges the men may have faced while working to end slavery?

- Why do you think I chose this book for us to read today?

Exploring the Book (Reading Standards, Craft & Structure, Strand 5, Key Ideas & Details, Strand 1, and Integration of Knowledge & Ideas, Strand 7)

Talk about the title. Ask students what they think the title means. Then ask them what they think this book will most likely be about and who the book might be about. What do you think might happen? What information do you think you might learn? What makes you think that?

Take students on a book walk and draw attention to the following parts of the book: front and back covers, half title page, dedications, title page, illustrations, and afterword.

Setting a Purpose for Reading (Reading Standards, Key Ideas & Details, Strands 1–3)

Have students read to find out what motivates Frederick’s mother to make such a long journey each night and to what the title, Love Twelve Miles Long, refers. Encourage students to consider why the author, Glenda Armand, would want to share this story with children.

VOCABULARY (Language Standards, Vocabulary Acquisition & Use, Strands 4–6)

The story contains several content-specific and academic words and phrases that may be unfamiliar to students. Based on students’ prior knowledge, review some or all of the vocabulary below. Encourage a variety of strategies to support students’ vocabulary acquisition: look up and record word definitions from a dictionary, write the meaning of the word or phrase in their own words, draw a picture of the meaning of the word, create a specific action for each word, list synonyms and antonyms, and write a meaningful sentence that demonstrates the definition of the word.

Content Specific

candlelit sunup The Buzzard Lope corn-shucking loft

Africa Pigeon Wing The Corn Shucking Dance White House moonlit

pantry

Academic

reflected ache wondering wise chuckling measure

lightens soul first second third fourth

fifth sixth seventh eighth ninth tenth

eleventh twelfth harvest burden gently sadness

yawning slaves masters knelt worn autobiography

presence freedom enslaved precious confidence

AFTER READING

Discussion Questions

After students have read the book, use these or similar questions to generate discussion, enhance comprehension, and develop appreciation for the content. Encourage students to refer to passages and/or illustrations in the book to support their responses. To build skills in close reading of a text, students should cite evidence with their answers.

Literal Comprehension (Reading Standards, Key Ideas & Details, Strands 1 and 3)

- Why doesn’t Frederick live with his mother? How does Frederick feel about living with Aunt Katy?

- What does Frederick’s mother think about as she walks to visit with Frederick? What does she do or think about to keep from feeling bored, sore, and tired?

- What obstacles (geography, historical period, physical, emotional) does Frederick’s mother face to see her son? How does she try to solve them?

- What is Frederick’s mother wish for her son?

- What is corn shucking?

- How does Frederick react to his mother’s story each time he hears it?

- What did it mean to be enslaved in Frederick Douglass’s time?

Extension/Higher Level Thinking (Reading Standards, Key Ideas & Details, Strand 2 and 3 and Craft & Structure, Strand 4–6)

- How does Frederick’s mother feel about walking twelve miles to visit Frederick?

- How is Frederick’s mother persistent? How is she fearless? What other character traits does she exhibit?

- How does Frederick’s mother teach Frederick hope and optimism through her words and actions?

- What if Frederick’s mother lived fifteen or twenty miles away from Frederick? How do you think she would handle the situation based on what you know of her character traits?

- What words or phrases does the author, Glenda Armand, use to show that Frederick misses his mother?

- What are the central ideas of this story? What does the author want readers to know about slavery? What does the author want readers to understand about family?

- The story is mostly told through dialogue, specifically the conversation between Frederick and his mother. What is the purpose of using dialogue to tell the story?

- Why is it so important for Frederick to know his mother loves him the morning after she has left?

- Why do you think Frederick asks his mother to tell him how she walks and how she makes the journey shorter? Why do you think Frederick wants to hear the answer again after already having heard it many times before?

- How does this journey at night benefit Frederick and his mother?

- Think about the relationship between Frederick and his mother. How would describe it? Think about the illustrations, how Frederick and his mother talk to each other, and their actions throughout the story. Why might the author want us to admire their relationship? Do you think the author wants the reader to aspire to have the same kind of relationship with someone? Why or why not?

- How might things be different if Frederick and his mother were free?

- What impact has slavery had on Frederick and his mother and their relationship?

- How do the illustrations help readers understand who Frederick and his mother are, their character traits, and their motivations? What can readers learn from the illustrations about Frederick and his mother?

- Read the afterword. What information about Frederick Douglass do you learn that is not in the text? What is the purpose of the afterword?

Literature Circles (Speaking & Listening Standards, Comprehension & Collaboration, Strands 1–3 and Presentation of Knowledge & Ideas, Strands 4–6)

**If you use literature circles during reading time, students might find the following suggestions helpful in focusing on the different roles of the group members.

- The Questioner might use questions similar to the ones in the Discussion Question section of this guide.

- The Passage Locator might look for lines or sentences in the story that express Frederick’s optimism. • The Illustrator might illustrate what Frederick’s mother dreams about on the eleventh mile.

- The Connector might find the book Frederick Douglass: The Last Day of Slavery and connect how his relationship with his mother influenced his views of slavery.

- The Summarizer might provide a brief summary of the group’s reading and discussion points for each meeting

- The Investigator might look for information about the lives of enslaved people on a plantation during the early 1800s.

*There are many resource books available with more information about organizing and implementing literature circles. Three such books you may wish to refer to are: GETTING STARTED WITH LITERATURE CIRCLES by Katherine L. Schlick Noe and Nancy J. Johnson (Christopher-Gordon, 1999), LITERATURE CIRCLES: VOICE AND CHOICE IN BOOK CLUBS AND READING GROUPS by Harvey Daniels (Stenhouse, 2002), and LITERATURE CIRCLES RESOURCE GUIDE by Bonnie Campbell Hill, Katherine L. Schlick Noe, and Nancy J. Johnson (Christopher-Gordon, 2000).

Reader’s Response (Writing Standards, Text Types & Purposes, Strands 1–3 and Production & Distribution of Writing, Strands 4–6)

Use the following questions and writing activities to help students practice active reading and personalize their responses to the book. Suggest that students respond in reader’s response journals, essays, or oral discussion. You may also want to set aside time for students to share and discuss their written work.

- Over the course of her journey, Frederick’s mother reflects on and remembers her day, her son, and her hope for the future. What do you think about when you want to feel more hopeful? What motivates you not to give up when something gets tough? Who inspires you? What makes these memories important?

- Which parts of the book did you connect to the most? Which parts of the story did you connect to the least? Why? What memory can you share of listening to a story told by an adult you love or are close to, or of a time when you were apart?

- When Frederick Douglass felt sad the morning after his mother left, he remembered what she had told him she thinks about when she makes her journey. Why do you think that made him feel better? What do you think about or do when you feel lonely or sad? How do you think looking up, praying, smiling, singing, dreaming, and/or dancing might help people feel better?

- Have students write a book recommendation for Love Twelve Miles Long explaining why they would or would not recommend this book to other students.

ELL Teaching Activities (Speaking & Listening Standards, Comprehension & Collaboration, Strands 1–3 and Presentation of Knowledge & Ideas, Strands 4–6) (Language Standards, Vocabulary Acquisition & Use, Strands 4–6)

These strategies might be helpful to use with students who are English Language Learners.

- Assign ELL students to partner-read the story with strong English readers/speakers. Students can alternate reading between pages, repeat passages after one another, or listen to the more fluent reader.

- Have each student write three questions about the story. Then let students pair up and discuss the answers to the questions.

- Depending on students’ level of English proficiency, after the first reading:?• Review the illustrations in order and have students summarize what is happening on each page, first orally, then in writing. ?• Have students work in pairs to retell either the plot of the story or key details. Then ask students to write a short summary, synopsis, or opinion about what they have read.

- Have students give a short talk about what they admire about a character or central figure in the story.

- The book contains several content-specific and academic words that may be unfamiliar to students. Based on students’ prior knowledge, review some or all of the vocabulary. Expose English Language Learners to multiple vocabulary strategies. Have students make predictions about word meanings, look up and record word definitions from a dictionary, write the meaning of the word or phrase in their own words, draw a picture of the meaning of the word, list synonyms and antonyms, create an action for each word, and write a meaningful sentence that demonstrates the definition of the word.

INTERDISCIPLINARY ACTIVITIES (Introduction to the Standards, page 7: Student who are college and career ready must be able to build strong content knowledge, value evidence, and use technology and digital media strategically and capably)

Use some of the following activities to help students integrate their reading experiences with other curriculum areas. These can also be used for extension activities, for advanced readers, and for building a home-school connection.

Social Studies (Reading Standards, Integration of Knowledge & Ideas, Strands 7 and 9) (Writing Standards, Research to Build & Present Knowledge, Strands 7 and 8)

- Have students investigate Frederick Douglass’s adult life. How did he escape and gain freedom? What did he do to help other enslaved people get free? What is an abolitionist? What challenges did Frederick Douglass face in getting people to change their minds about slavery? How did his own life story help him persuade others that slavery was wrong?

- Help students research enslaved families. Look at child-appropriate history resources such as the Library of Congress or PBS (located in the background section of this guide). What happened to children born into slavery? What jobs did children do on farms? How did families stick together? What happened to families during the period of slavery? What happened to split families after the Civil War and the emancipation of those who had been slaved?

- After reading Love Twelve Miles Long, read about Frederick Douglass’s childhood and time in slavery, such as Frederick Douglass: The Last Day of Slavery. Compare the text structure, illustrations, tone, and central ideas of both biographies. Compare the character traits of Frederick in both books. What central ideas do the authors want readers to learn about slavery and the historic figure, Frederick Douglass? How did his childhood experiences prove to Frederick Douglass that slavery was wrong and unjust?

- Have students read another book about slavery, such as Lee & Low’s Seven Miles to Freedom, The Secret to Freedom, or Up the Learning Tree. What actions do these people who are enslaved take to gain their freedom? What character traits do these figures or characters have? How can these books be used to prove the cruelty of slavery? How might these books inspire activism against racism? Why might authors want to share the history of slavery and the stories of courageous figures with children today?

Writing (Writing Standards, Text Types & Purposes, Strand 1 and Production & Distribution of Writing, Strand 4)

- Think about the themes of the book and the relationship between Frederick and his mother. Write to your teacher to make a case for the holiday on which it would be best to read Love Twelve Miles Long. Why would this book be great for Christmas, Valentine’s, Mother’s Day, or some other day?

- Argue how this story of Frederick Douglass and his mother is relevant today. Students may focus on the significance of family relationships or discrimination. What kinds of situations exist today where children and parents don't always get to be together? How does the story demonstrate the importance of parent-child relationships? Even though slavery was long ago abolished in the United States, what situations still exist where people might be mistreated because of the color of their skin?

- Look back over what Frederick’s mother does for each mile to help pass the time as she gets closer to Frederick. What if she had to walk thirteen miles one night, instead of twelve? What would you recommend she do to help her walk that extra mile? Write a passage for the story that tells what Frederick’s mother does on the thirteenth mile.

Mathematics (Mathematics Standards, Measurement & Data, Strands 1–2 and Operations & Algebraic Thinking, Strand 1)

- Frederick’s mother walks twelve miles. Convert that to yards and kilometers.

- Take students to the sports track in the schoolyard or to a large field and have them walk one mile. Time how long it takes students to walk that mile. Based on each student’s pace for walking one mile, have them compute the time it would it take to walk twelve miles. If time and fitness permit, have students run a mile. Then, based on each student’s running pace, have them compute the time it would take to run twelve miles. You may also wish to have students record their times for one mile and twelve miles on a graph.

- 3.Have students look at a map of their community or town to see how far they could go if they were to walk twelve miles from school. With your school as the starting point, where would students end up if they went twelve miles north, east, south, and west?

Home-School Connection (Speaking & Listening Standards, Comprehension & Collaboration, Strands 1 and 2) (Writing Standards, Text Types & Purposes, Strand 2 and Research to Build & Present Knowledge, Strand 7)

- 1. Encourage students to talk with their parents, grandparents, or guardians about their bedtime rituals and then write about the conversation. Describe the stories you love to hear again and again. What activities do you do to spend time with this person? What do you do together to get ready for bed? Why is this time special to you?

- 2. Imagine or think of a time when your parent, grandparent, older sibling, guardian, or other special person in your life wasn’t able to visit you for a week. Write a letter to this person. Tell what you miss about your time together, what you are looking forward to doing the next time you see the person, and what has been going on in your life while you have been apart. Share your daily activities and any challenges you face.

About This Title

Guided Reading:

ULexile:

AD530LInterest Level:

Grades 1 - 6Reading Level:

Grades 2 - 3Themes

United States History, Slavery, Identity/Self Esteem/Confidence, Responsibility, Religion/Spiritual, Overcoming Obstacles, Mothers, History, Heroism, Families, Dreams & Aspirations, Discrimination, Childhood Experiences and Memories, African/African American Interest, Biography/Memoir, Poverty, Empathy/Compassion, Gratitude, Optimism/Enthusiasm, People In Motion, Persistence/Grit, Realistic Fiction, Self Control/Self Regulation, Pride

Collections

Civil Rights Book Collection, Black History Collection Grades K-2, Mother's Day Collection, New Voices Award Winners & Honors Collection, Appendix B Diverse Collection Grades K-2, Appendix B Diverse Collection Grades 3-6, African American English Collection Grades 3-6, Historical Fiction Grades PreK-2, Fluent Dual Language , Persistence and Determination Collection, Courage and Bravery Collection, Fluent English, Black History Paperback Collection, African American Collection English 6PK, English Guided Reading Level U, Social and Emotional Learning Collection, Positive Relationships Collection, Teaching about Slavery Collection, Juneteenth Webinar Collection, Reconstruction Webinar Collection

Want to know more about us or have specific questions regarding our Teacher's Guides?

Please write us!general@leeandlow.com Terms of Use