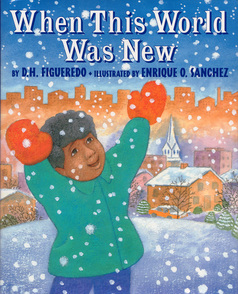

TEACHER'S GUIDE FOR:

When This World Was New

By D. H. Figueredo

Illustrations by Enrique O. Sanchez

Synopsis

Danilito and his parents leave their homeland in a warm Caribbean island nation and come to live in the United States. Although excited, they are filled with trepidation at the prospect of life in a place where they don’t speak the language or know the customs. The concerns of finding work and settling into a new school and neighborhood are uppermost in everyone’s mind, but a magical, unexpected snowfall raises everyone’s spirits and hopes about their new home in America.

In a general way, When This World Was New reflects the experiences of both the author and illustrator. D. H. Figueredo, the author, and Enrique O. Sanchez, illustrator, are natives of Latin American countries. Figueredo came to the United States from Cuba when he was a teenager. Sanchez was born in the Dominican Republic and came to the United States when he was 20.

Background

Immigration—the leaving of one’s native country to settle in another country—is often prompted by economic hardships, persecution, war, political unrest, disasters such as famines, or epidemics. People move to another country to escape one or more of these situations and look forward to making a better life for themselves and their families. For millions of people, the United States has long been a receiving nation of the world’s immigrants and refugees. During the 1950s to 1980s about 700,000 people came to the United States from Cuba because of political events surrounding the Communist takeover and subsequent Castro dictatorship there. Poverty and unemployment in the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Jamaica drew about 900,000 people to the United States in the 1970s and 1980s. Today, both Cuba and the Dominican Republic are in the top 10 sources of immigrants to the United States.

| Teacher Tip |

| You may wish to use this book as part of your celebration of Hispanic Heritage Month this fall (September 15–October 14). This is also an excellent selection for a back-to-school book, especially if there are students in your class who are newly arrived from other countries. |

Before Reading

Prereading Focus Questions

Before sharing When This World Was New with students, you may wish to have students discuss one or more of the following questions as a motivation for reading.

- Have you and your family ever moved? What was the experience like? How did you feel?

- What does the word “immigrant” mean? Do you know any people who are recent immigrants? From which countries did they come?

- When you face new situations, how do you feel? How do you act? Why?

- Can you speak more than one language? How would you communicate if you moved to a place where people spoke a language you did not know?

Exploring the Book

Write the book title When This World Was New on the chalkboard. Invite students to tell what they think the title means. Have students write down their predictions of what the story might be about. Be sure to revisit students’ predictions after reading the book.

Display the cover and invite students to comment on the art. How might the cover picture relate to the title? What do you notice about the boy? What might he be thinking?

Setting a Purpose for Reading

Have students write down two questions they hope will be answered by reading the book. You might get students thinking with an example such as: Where does the story take place?

Point out that the book was listed as one of the Best Children’s Books of the Year (for books published in 1999) by Bank Street College. As they read, ask students to look for reasons why they think the book received this honor.

Vocabulary

Write the following words from the story on the chalkboard

| stingrays | terminal | vanished |

| surface | comet | trudged |

| ramp | meteor | embraced |

Partner students for a vocabulary hunt. As students come across these words in their reading, have them try to use context to figure out the meanings. Have the partners take turns writing down what they think each word means while the other partner looks up the word in a dictionary. Students can then compare definitions and make any necessary adjustments to their own definition. As a follow-up, ask students to choose four of the words and illustrate them.

After Reading

Discussion Questions

Use these and similar questions to help students review the book and develop comprehension. Encourage students to refer to passages in the book and parts of the illustrations that support their answers.

- How do Danilito and his parents travel to their new country? How do they feel on their journey?

- Why is Danilito both excited and scared when they land?

- Why is Uncle Berto so happy to see them?

- What do the city lights remind Danilito of? How do you think this makes him feel?

- What are some things the family is worried about as they arrive in the United States?

- How does Uncle Berto prepare for his relatives’ arrival?

- Why does Danilito say he shouldn’t go to school? How does Papá respond?

- What is the magic that Danilito sees? Why is it magic to him?

- How do Danilito’s and Papá’s footprints change as they climb up the hill? How might the footprints in the snow be like the path the family follows in their new country?

- Why is Danilito less scared as his uncle drives him to school?

- Think about the way the story ends. Why doesn’t it show and tell about what happens at the factory and at school? What do you think the author and illustrator are saying with the picture of Danilito skating on the last page?

- Think about the title of the story. What made “this world” new?

Literature Circles

If you use literature circles during reading time, students might find the following suggestions helpful in focusing on the different roles of the group members.

- The Questioner might use questions similar to those in the Discussion Question section to help group members explore the text.

- The Passage Locator might look for descriptive text that describes the places in the book.

- The Illustrator might draw the places mentioned but not pictured in the book such as the factory where Papá will work or the school that Danilito will attend.

- The Connector might find other books about children who are immigrants to the United States.

- The Summarizer might provide a brief summary of the pages that the group is discussing.

- The Investigator might research information about present day life in Caribbean or Latin American countries from which many immigrants have come to the United States.

There are many resource books available with more information about organizing and implementing literature circles. Three such books you may wish to refer to are: *Getting Started with Literature Circles* by Katherine L. Schlick Noe and Nancy J. Johnson (Christopher-Gordon, 1999), *Literature Circles: Voice And Choice in Book Clubs and Reading Groups* by Harvey Daniels (Stenhouse, 2002), and *Literature Circles Resource Guide* by Bonnie Campbell Hill, Katherine L. Schlick Noe, and Nancy J. Johnson (Christopher-Gordon, 2000).

Reader's Response

Use the following questions or similar ones to help students practice active reading and personalize what they have read. Suggest that students respond in reader’s notebooks or in oral discussion.

- How do the illustrations in this book add to your understanding of the story? Give two examples.

- What is your favorite part of this book? Why?

- How does this book affect your attitude toward newcomers?

- What would you tell another reader about this book? Would you recommend it? Why?

Other Writing Activities You may wish to have students participate in one or more of the following writing activities. Set aside time for students to share and discuss their work.

- What do you think Danilito’s first day at school was like? Did he have a hard time? Did he make friends? How did he cope with a new place, new faces, and a new language? Write a paragraph telling what you think happened.

- Make a timeline of Danilito’s feelings on his journey and arrival in the United States. For each mark on the timeline, write what happens and how Danilito feels.

- Pretend you are Danilito. Write a letter to a friend or relative at home about your experiences in your new country.

- Write a poem about how Danilito and his father enjoyed the snow.

ELL/ESL Teaching Strategies

These strategies might be helpful to use with students who are English language learners or who are learning to speak English as a second language. 1. Make a tape recording of the story for students to listen to as they follow along in the book. 2. Point to concrete nouns in the text and have students find those items in the illustrations. For example: planes, suitcases, cars, buildings, house, hill, cans, coat, snow, window, ball, footprints. 3. Read aloud a sentence and have students repeat the sentence after you, pointing to each word as they read. 4. Break down large chunks of information or long text passages into smaller chunks so students can comprehend more easily.

Interdisciplinary Activities

To help students integrate their reading experiences with other curriculum areas, you might try some of the following activities.

Language Arts

When This World Was New offers good examples of figurative language such as similes and metaphors. Introduce and discuss the following:

| Simile | “Cars sped past us as fast as meteors.” |

| Ask students to identify the two things being compared. (cars and meteors) | |

| Metaphor | “Outside, there were millions of white rose petals floating downwards.” |

| Ask students what the millions of white rose petals are. (snow flakes) |

Have students reread the story and find other examples of similes and metaphors. Talk about how similes and metaphors help paint word pictures. If appropriate, have students compare the two types of figurative language.

Social Studies

- Ask students to find stories about immigrants from other countries in newspapers and news magazines. Create a bulletin board using a world map. Tack the stories around the map and pin flags to the countries they are about. Attach the flags to the news stories with colored yarn.

- Invite any students who have come from other countries to share their experiences with the class. Remind students that just as immigrants have many things to learn, they also have many things to share. Students might share photographs, postcards, music, foods, or special mementos from their homelands.

- On a world map or globe, have students locate the islands in the Caribbean. Have students brainstorm a list of questions they would like answered about each island. Then have small groups each choose one of the islands and research the answers to the questions. Encourage students to present their findings using a variety of media.

Science

Students might research how climate and weather in New York City differ from that of Caribbean countries. Have students make a chart or graph to show the differences.

Citizenship

Brainstorm with students ways to welcome newcomers to your class. Make a list of students’ ideas. Then work with the class to develop materials that might be helpful to someone from another country. These might include explanations for common idioms and slang terms, a map of your classroom and/or school, and picture dictionaries.

About the Author

D. H. Figueredo is a native of Guantanamo, Cuba. He now lives in New Jersey with his wife and two daughters. He holds master’s degrees in library science and comparative literature and works as a library director at Bloomfield College and as a literature professor at Montclair State University. “I write during lunch time,” says Figueredo. “I haven’t taken lunch in the last five years!”

About the Illustrator

Enrique O. Sanchez grew up in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic. He studied architecture and painting at Santo Domingo University and later at the Belles Artes Institute. He moved to New York City in the 1960s and worked as a graphic designer for Children’s Television Workshop’s “Sesame Street” when the show was first starting up. He continued to work in theater and television design while concentrating on his fine art painting. His work has been displayed in galleries around the United States and is part of many corporate collections. Sanchez and his wife live in East Burke, Vermont.

In addition to being honored by Bank Street College as on of the Best Books of the Year (1999), When This World Was New was a “Choices” selection from the Cooperative Children’s Book Center.

About This Title

Guided Reading:

MLexile:

AD600LInterest Level:

Grades K - 3Reading Level:

Grades 2 - 2Themes

Weather/Seasons/Clothing, Similarities and Differences, Identity/Self Esteem/Confidence, Overcoming Obstacles, Latino/Hispanic/Mexican Interest, Immigration, Home, Fathers, Families, Cultural Diversity, Childhood Experiences and Memories, Poverty, Optimism/Enthusiasm, Courage, New York, Realistic Fiction

Collections

English Fiction Grades PreK-2, Early Fluent Dual Language, Early Fluent English, Latin American English Collection Grades 3-6, Bilingual English/Spanish and Dual Language Books , New York Past and Present Collection, RITELL PreK-2 Collection, Appendix B Diverse Collection Grades K-2, Realistic Fiction Collection Grades PreK-2, Immigration Collection, Dual Language Collection English and Spanish, Dual Language Levels J-M Collection, Pedro Noguera Diverse Collection Grades PreK-2, Latin American Collection English 6PK, Natural Disaster & Displacement Collection, English Guided Reading Level M

Want to know more about us or have specific questions regarding our Teacher's Guides?

Please write us!general@leeandlow.com Terms of Use